When I was elected President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) in 2022, I said I would listen to and represent women and our members and drive political and health leaders to improve the quality and safety of women’s health. It was clear that despite the hard work of professionals across the health service, gynaecology waiting times were only getting worse, with women still not receiving the timely treatment and care they needed.

Building on the excellent work in our Left for too long report, we set out to deepen our understanding of gynaecology waiting lists in the UK national health services and ask women and professionals about their experiences and what solutions they believed would help the recovery of gynaecology waiting lists and improve care for women.

This new report illustrates that waiting times for gynaecology have worsened in all parts of the UK, with women living in areas of higher deprivation often waiting the longest for treatment. Behind these numbers are real women living in extreme and often avoidable pain. Women who are desperate for help and support, waiting for months and in some cases years, for vital treatment and care.

As a frontline healthcare professional, I strive to do my best for the women I look after. Our duty as professionals is to support each other and ensure we all deliver the highest quality of care to every woman and girl we care for.

Our research made clear that professionals across the entire system are deeply concerned for women waiting for gynaecology treatment, and report their own moral injury at seeing their patients in distress. However, they are not being given the funding, resources, time and capacity to deliver the high-quality care they want to provide.

The current state of gynaecology waiting times across the UK should concern not just the women directly impacted and the professionals caring for them. It should concern all of us that in 2024, women, who make up 51% of the population of the UK, are being prevented from living full, healthy lives and reaching their potential.

The situation with gynaecology waiting lists has reached a critical juncture. The new government in England, and governments across the devolved nations, must ask themselves how much longer underinvestment and deprioritisation of gynaecology care can continue, and if they will rise to the challenge of delivering for women now and in the future.

This would have huge benefits, not just for the women waiting for care but also the healthcare professionals supporting them. As the NHS Confederation’s recent report demonstrated, for every additional £1 of public investment in obstetrics and gynaecology services per woman in England, there is an estimated return on investment of £11 which is an estimated £319 million return to the economy.

I am immensely proud to share the RCOG’s new research, and indeed, deeply grateful to all the women and healthcare professionals who shared their experiences with us. Their voices are at the heart of this report, and it is their experiences that must compel us all, but particularly the governments of the UK, to act.

Ranee Thakar, RCOG President

RCOG Women's Network

Involving women and people with lived experience is crucial to the work of the RCOG and improving gynaecology services. The RCOG Women’s Network has contributed to this report throughout its development.

We would like to thank the women and people who so generously shared their experiences of waiting for gynaecology care through our survey and as part of our series of focus groups that helped shape this report and recommendations. Thousands of women and people shared their experiences of navigating daily life with serious and progressive conditions without the right care and support, and it is truly heart-breaking to hear the extent of their pain and suffering.

We know gynaecology waiting times have worsened since the pandemic, but this has been an ongoing issue for far too long. There are women waiting for vital treatment for unacceptable periods of time, feeling isolated and with no part of their life left untouched by the impact of their condition and symptoms.

We also know there are women for whom the system is even harder to navigate due to inequalities that can create additional challenges in accessing support and resources. The government must listen to patients and the organisations that support them, involve them in decision making, service design, and prioritise addressing inequalities so that the NHS works for and meets the needs of all patients.

Urgent support for women and people waiting is needed now, but we also urge all governments across the UK to commit to long term investment to ensure timely and compassionate care can be provided for women now and in the future.

Building on the findings documented in the RCOG’s previous report, Left for too long, the College commissioned new primary research to deepen our understanding of the size and impact of gynaecology waiting times on women and professionals across the system in the UK today.

In this new report, we demonstrate that waiting lists for gynaecology in the UK have increased by a third since we wrote our previous report in 2022.1 Three quarters of a million women across the UK are now waiting for gynaecology treatment, and the data available nationally only captures a snapshot of the problem.

There are thousands more women likely to be waiting for other care, including diagnostic tests to confirm their condition in the first place or essential care following treatment.

In our research with women impacted by these lengthy waits, we have heard about the continued and worsening impact on their lives. Women waiting for care are commonly in constant, chronic, and debilitating pain, struggling to manage worsening physical and mental health symptoms.

A quarter of the women we surveyed for this report said they had attended A&E because of their symptoms, with more than one in ten going on to require emergency interventions, such as blood and iron transfusions. Chronic waiting times are directly preventing women from living their lives to the fullest. Not only is this deeply unfair to women, but it impacts all of us, given women's integral contributions to wider society and the economy.

Professionals across the system were united in their deep concern for their patients, emphasising the moral injury and helplessness they felt as a result of not being able to expedite waiting times or offer the care they want to provide, due to a lack of capacity and resources.

The root causes of the crisis in gynaecology care are undoubtedly a combination of both NHS-wide long term issues and specific challenges experienced by gynaecology as a specialty. Funding, including the levels set across the UK, the short-termism of recent decisions and the lack of sufficient funding for NHS workforce and core infrastructure like estates, is at the heart of capacity issues. However, the continued lack of prioritisation of women’s health by Government – and gynaecology by extension – explains why gynaecology is so challenged as a speciality.

Gynaecology has historically been perceived as less important in wider elective recovery, and this has resulted in an increasing number of complex cases, disease progression, emergency admissions and women living in pain and distress: all of which are preventable.

System-wide issues and the crisis in gynaecology have also left professionals at every level with little time to receive or provide training, creating a critical risk in how the NHS will deliver high quality gynaecology care now and in the future.

The RCOG warned of these risks in Left for too long, and we are now living with the consequences of insufficient action. The question for governments across the UK is what they will do to break this cycle.

There are some green shoots. We have seen some progress in some areas of women’s health since we published Left for too long. This includes the work of Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) and the National Consultant Information Programme, investment in Women’s Health Hubs across England,2 and women’s health plans and strategies established in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, with a plan due to be published in Wales.3

But implementing these plans is not moving far or fast enough for the women waiting for gynaecology care, nor for the professionals across the system who tell us how gravely concerned they are for their patients.

Both women and professionals are still waiting for a way forward: plans for the short and longer term need to be implemented, and this will require focus and funding, so that health systems can support professionals to deliver the best care they can to every woman waiting.

Building on the findings documented in the RCOG’s previous report, Left for too long, the College commissioned new primary research to deepen our understanding of the size and impact of gynaecology waiting times on women and professionals across the system in the UK today.

In this new report, we demonstrate that waiting lists for gynaecology in the UK have increased by a third since we wrote our previous report in 2022.1 Three quarters of a million women across the UK are now waiting for gynaecology treatment, and the data available nationally only captures a snapshot of the problem.

There are thousands more women likely to be waiting for other care, including diagnostic tests to confirm their condition in the first place or essential care following treatment.

In our research with women impacted by these lengthy waits, we have heard about the continued and worsening impact on their lives. Women waiting for care are commonly in constant, chronic, and debilitating pain, struggling to manage worsening physical and mental health symptoms.

A quarter of the women we surveyed for this report said they had attended A&E because of their symptoms, with more than one in ten going on to require emergency interventions, such as blood and iron transfusions. Chronic waiting times are directly preventing women from living their lives to the fullest. Not only is this deeply unfair to women, but it impacts all of us, given women's integral contributions to wider society and the economy.

Professionals across the system were united in their deep concern for their patients, emphasising the moral injury and helplessness they felt as a result of not being able to expedite waiting times or offer the care they want to provide, due to a lack of capacity and resources.

The root causes of the crisis in gynaecology care are undoubtedly a combination of both NHS-wide long term issues and specific challenges experienced by gynaecology as a specialty. Funding, including the levels set across the UK, the short-termism of recent decisions and the lack of sufficient funding for NHS workforce and core infrastructure like estates, is at the heart of capacity issues. However, the continued lack of prioritisation of women’s health by Government – and gynaecology by extension – explains why gynaecology is so challenged as a speciality.

Gynaecology has historically been perceived as less important in wider elective recovery, and this has resulted in an increasing number of complex cases, disease progression, emergency admissions and women living in pain and distress: all of which are preventable.

System-wide issues and the crisis in gynaecology have also left professionals at every level with little time to receive or provide training, creating a critical risk in how the NHS will deliver high quality gynaecology care now and in the future.

The RCOG warned of these risks in Left for too long, and we are now living with the consequences of insufficient action. The question for governments across the UK is what they will do to break this cycle.

There are some green shoots. We have seen some progress in some areas of women’s health since we published Left for too long. This includes the work of Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) and the National Consultant Information Programme, investment in Women’s Health Hubs across England,2 and women’s health plans and strategies established in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, with a plan due to be published in Wales.3

But implementing these plans is not moving far or fast enough for the women waiting for gynaecology care, nor for the professionals across the system who tell us how gravely concerned they are for their patients.

Both women and professionals are still waiting for a way forward: plans for the short and longer term need to be implemented, and this will require focus and funding, so that health systems can support professionals to deliver the best care they can to every woman waiting.

The UK Government must deliver help now to improve care for women waiting:

1. Continue to promote or expand schemes so that women can access free products to manage symptoms such as heavy menstrual bleeding and incontinence.

2. Urgently prioritise improving communication with women waiting for gynaecology care and treatment, including giving women clarity on how long they should expect to wait.

This work must include national, system and local leads from across the UK to ensure this is addressed at every level of operational delivery.

3. Expand the accessible information and advice that is available at a national level which can be accessed on relevant NHS websites in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This should be co-produced with service users.

4. Direct relevant system and local leads to urgently produce easy-to-read accessible bespoke summaries of what local networks and resources are available to women waiting on gynaecology lists so they can access additional support in their local communities, close to home.

To support professionals, we recommend that governments across the UK:

5. Provide health services with the resources they need so they can protect gynaecology services against operational pressures, ensuring greater theatre and diagnostic capacity for gynaecology.

6. Build, enable, and incentivise protected training time in gynaecology as part of any elective recovery plan, to future-proof care provision.

7. Develop accessible professional guidance about supporting women on waiting lists, ensuring it is easily accessible nationally.

8. Consider targeted funding at a national level to expedite the longest waits, to ensure equity.

9. Work with leads at all levels of the system to develop or consolidate strategic support networks and partnerships, particularly those between primary and secondary care, to improve delivery of care.

10. Thank all professionals at every part of the pathway working in women’s health, acknowledging the specific challenges in the wider system that are unique to women’s health.

The UK Government must also act now to deliver for the future to ensure high-quality gynaecology care for every woman in the UK:

11. Commit to expanding Women’s Health Hubs in an equitable and sustainable way so that they can be established, to ensure all women, wherever they live, can access care and support to manage their health across their whole life course.

12. Set out how it plans to deliver, with sustainable funding attached, the future demand and supply requirements outlined in the Long Term Workforce Plan.

This should include plans to recruit professionals and deliver retention measures to encourage professionals to stay in the NHS.

13. Increase the levels of funding allocated to health across UK, including increased funding in devolved nations.

14. Implement measures to improve education and awareness of gynaecology in wider society and create better access to education and training for professionals in gynaecology care.

15. Consider how to build on existing digital initiatives, commit to expanding data collection in gynaecology and commit to ringfenced funding to enable research, patient participation, innovation and pilots to improve understanding and experiences of gynaecology.

In this report, we refer to ‘women’s health’, but it is important to acknowledge that it is not only women for whom it is necessary to access women’s health and reproductive services in order to maintain their gynaecological health and reproductive wellbeing. Gynaecological and obstetric services and delivery of care must be appropriate, inclusive, and sensitive to the needs of those individuals whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Our partners at LCP Analytics have used the publicly available data that has been published by the NHS England, Public Health Scotland, Stats Wales and the Northern Ireland Department for Health to develop our Elective Recovery Tracker. The NHS datasets used to create our dashboard record 'pathways' (individual entries on the waiting list) rather than people, which means if a patient is waiting for two procedures on the same wait list this will feature as two pathways.

Terms such as ‘women’, ‘people’, ‘cases’, ‘pathways’ ‘appointments’ are often used interchangeably when reporting waiting list numbers. In this report, we have used this data to provide illustrative examples to help the reader appreciate the scale and growth of waiting lists across the UK, and how many women are impacted by this.

The RCOG published our Left for too long report in April 2022. In it, we warned that gynaecology waiting lists across the UK had grown dramatically since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic: an increase of over 60% compared to pre-pandemic levels. Significant increases have been seen across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The latest data reveals that gynaecology waiting lists have continued to increase across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. In July 2024, the RCOG, with our partners Theramex and LCP Analytics, launched a publicly accessible dashboard that captures gynaecology waiting lists across the UK.

The total number of those waiting for gynaecology treatment across the UK has grown by a third compared to 2021 figures we used in our Left for too long report4 and by 112% compared to pre-pandemic numbers.5

As of June 2024, over three-quarters of a million women (763,694) across the UK are waiting for gynaecology care.6

Data shows that in August 2024, there were 592,662 people on the waiting list for gynaecology in England.7 This is an increase of almost a third compared to January 2022 statistics8 and 107% compared to February 2020.9

In England, the NHS target is for 92% of patients to have a referral-to-treatment time of less than 18 weeks. This measure is calculated from the day a referral is received by the hospital or gynaecology department, and ends when treatment begins.

In gynaecology, this could mean an admission to hospital for an operation or treatment, starting a treatment pathway outside of hospital, having a medical device fitted, or agreeing with the gynaecology team to ‘watch and wait’ ahead of possible further treatment or care.

The number of women waiting over 18 weeks from referral to treatment had already reached nearly 47,000 in February 2020, before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.10 That equated to 84% of women being treated within 18 weeks, with 16% of women waiting longer than 18 weeks for treatment.11

By January 2022, 40% of the women on the waiting list were waiting longer than the 18-week referral to treatment standard.12 This number has continued to increase, with nearly half of women now waiting over 18 weeks for treatment.13 Data shows a 482% increase in the number of women waiting longer than the 18-week national target compared to pre-pandemic levels.14

NHS England also measures the number of people waiting more than 52 weeks for treatment. In February 2020, there were just 66 women who had been on the gynaecology waiting list for over 52 weeks: as of July 2024, there were 27,671. Whilst overall the number of people waiting over 52 weeks has been on a downward trend since 2022, the number of women waiting over a year for treatment is still unacceptably high.

In England, the Integrated Care Boards that have the highest number of women on gynaecology waits per 100,000 of the population are typically clustered in the North West, South East and East of England.16 The data we currently have available cannot conclusively tell us why waits are so long in these areas, and the reasons may differ between areas.

For example, the North West has the highest number of new referrals, which may mean that waiting lists are being driven by a sharp rise in demand and they may be treating patients outside of their area. The East of England has one of the highest median waits for treatment,17 which could be driven by other reasons, such as challenges with NHS estates.18

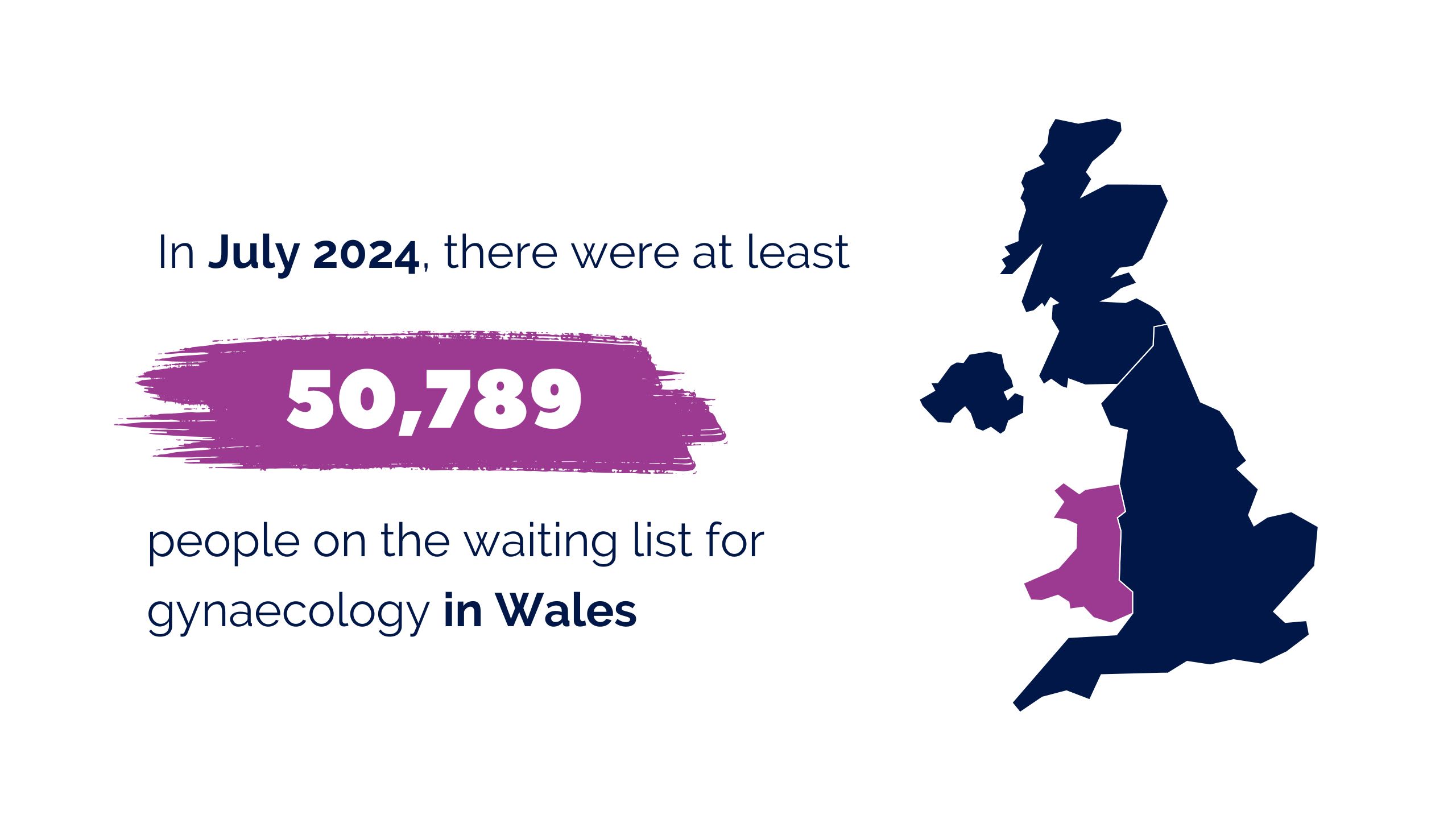

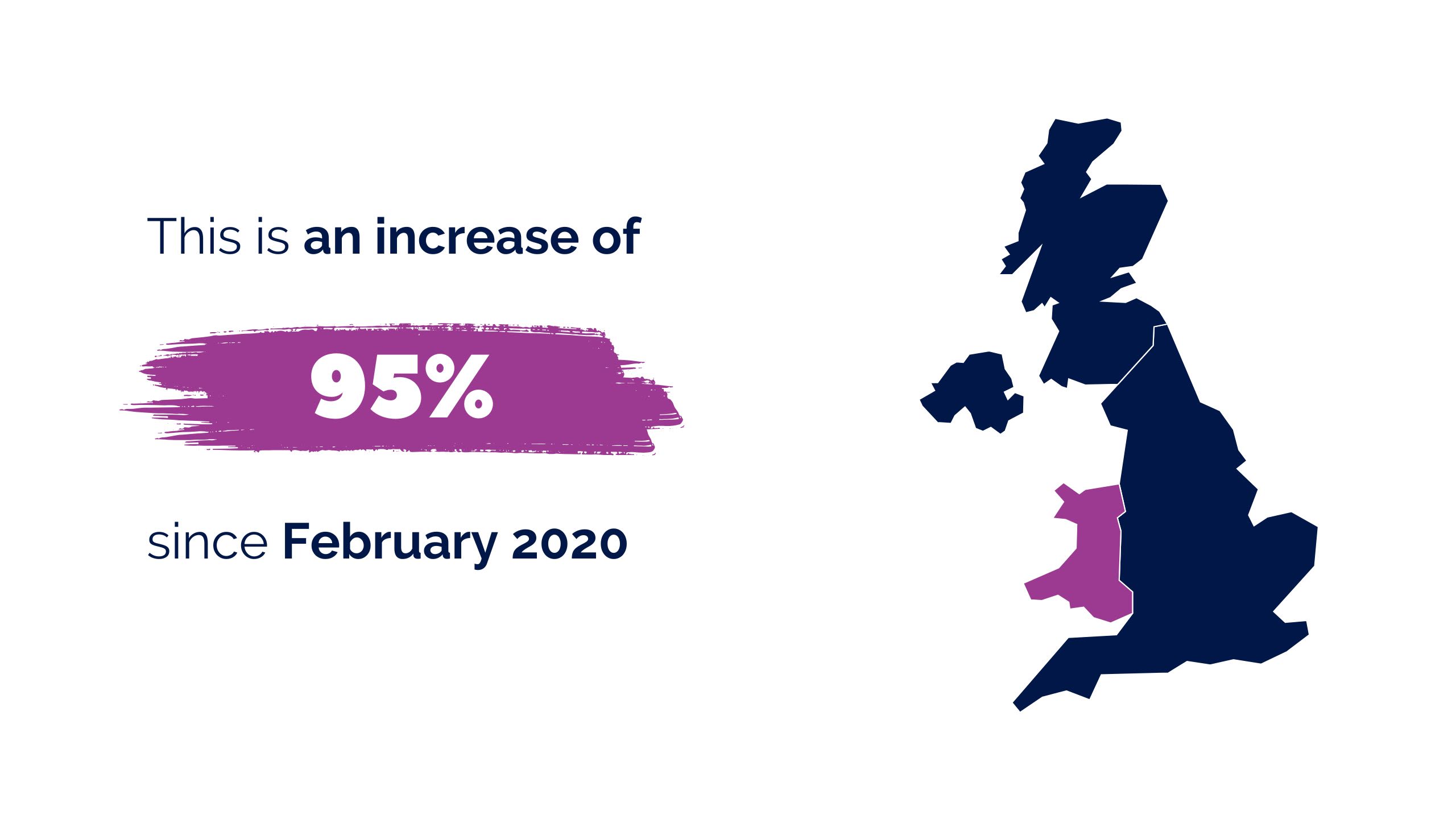

The most recent data available for Wales shows that, in July 2024, there were at least 50,789 people on the waiting list for gynaecology, an increase of 95% since February 2020,19 and we expect the real number is even higher, given instances of paused data submissions.

The referral-to-treatment target in Wales is that 95% of patients should be seen within 26 weeks. In Left for too long we demonstrated that by December 2021 there had been a 438% increase in women waiting more than 26 weeks from referral to treatment for gynaecology compared to pre-pandemic levels.20

There are now 24,534 women and people waiting over 26 weeks, a 496% increase compared to pre-pandemic levels.21 Nearly half of patients are currently waiting more than 26 weeks.22

The NHS in Wales also measures the number of patients waiting over 36 weeks for treatment. In February 2020, 823 women on the waiting list for gynaecology had waited over 36 weeks from referral to treatment.23 As of July 2024, 18,264 women had waited over 36 weeks, meaning that over a third of women (36%) on the waiting list are waiting over the national target of 36 weeks to start treatment.24

In Wales, the waiting lists for gynaecology per 100,000 patients are high across the Health Boards in the south of Wales, with numbers higher than some of the most challenged areas of England. The longest waiters are typically in the south, although the Betsi Cadwaladr Health Board in the north of Wales also has many of the longest waiters.

Again, the data we currently have available does not provide the rationale for these waiting times, but we know that Wales faces significant challenges with its NHS workforce25 and with high levels of deprivation, with more than one in eight people across Wales often or always struggling to afford essentials.26

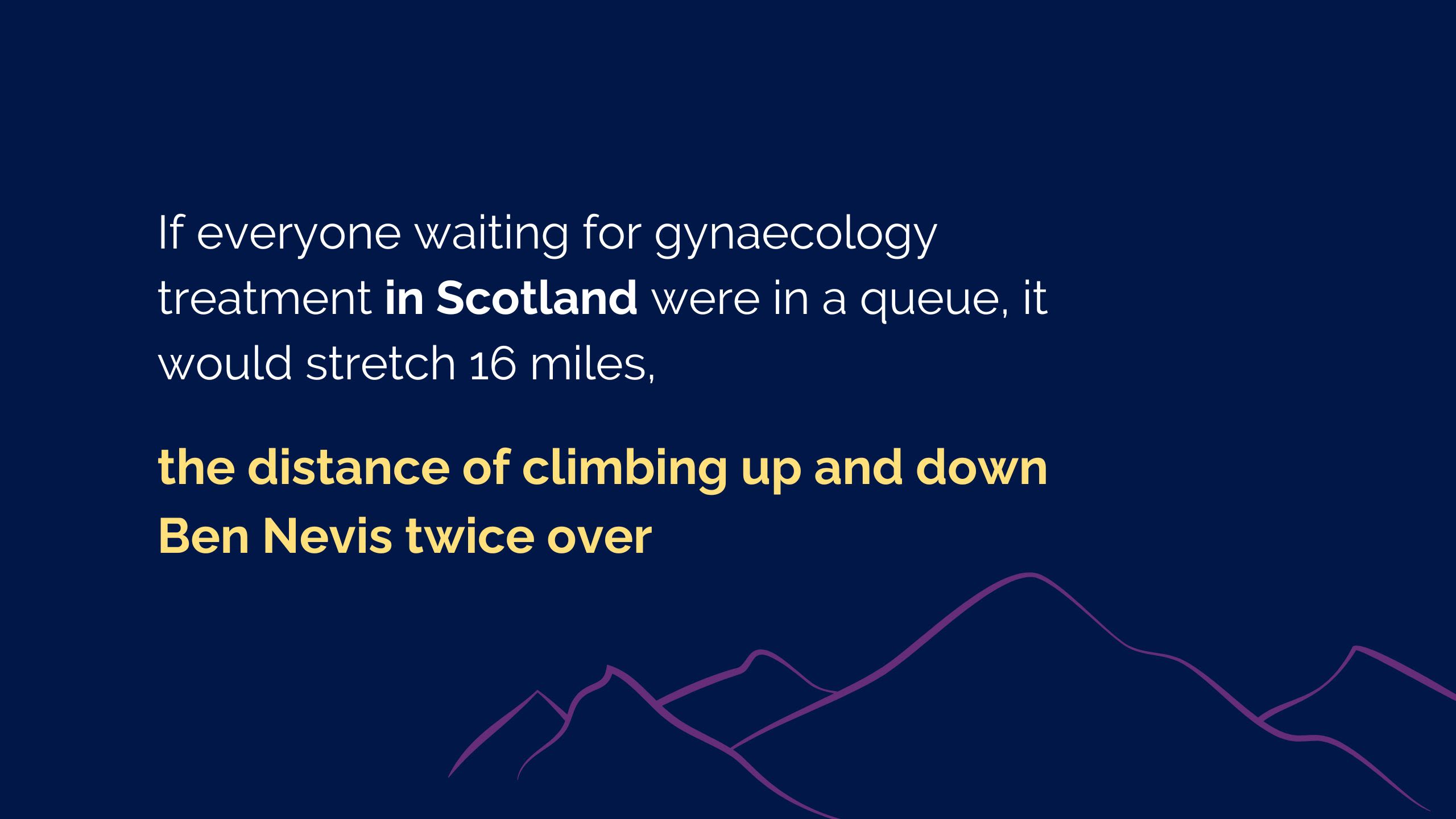

The most recent data available shows that in June 2024, 65,826 people were on the waiting list for gynaecology in Scotland, a 193% increase compared to February 2020 figures.27

The NHS in Scotland’s referral-to-treatment pathway for elective care is 18 weeks, underpinned by the Scottish Government target, which states that 90% of patients should move from referral through to treatment in less than 18 weeks. Under this 18-week target, the 14 Health Boards in Scotland must ensure patients are seen within 12 weeks of referral and, having received a diagnosis and agreed treatment, receive inpatient or day case treatment within 12 weeks.

Before the pandemic, the percentage of women and people waiting over 12 weeks for their initial outpatient appointment was only 13%.28 The latest data for June 2024 shows that this has continued to increase, with over 65% of women now waiting over 12 weeks.29

The highest number of waits for gynaecology care per 100,000 population are clustered around the west of Scotland, with Greater Glasgow having the highest concentration by population size.

Women in the east of Scotland, including Lothian and Tayside, also are experiencing long waits for care. Health inequalities may play a role in this, which the Scottish Government is working to address as outlined in its Women’s Health Plan.30

Data from June 2024 shows that an estimated 50,747 people were on the waiting list for gynaecology treatment in Northern Ireland.31 This is almost a 95% increase compared to the number of people waiting at the start of the pandemic.32

In Northern Ireland, waiting time targets are measured differently from those in the other parts of the UK. Northern Ireland targets look at individual parts of the pathway separately, including patients waiting for outpatient appointments, diagnostics and inpatient care.

Outpatient waiters are defined as the number of patients waiting for their first appointment in secondary care from a referral. The target is that 50% of patients should not wait more than nine weeks for an initial outpatient appointment, with no patients waiting over 52 weeks. As of March 2020, waiting lists were already long, with 25% of women on the list waiting over 52 weeks for an outpatient appointment.33

The waiting list for inpatient or day case treatment refers to patients waiting either for hospital admission overnight or for treatment within a day. At the start of the pandemic waiting lists for inpatient surgery already showed 30% of women waiting over a year for surgery.34 Across both outpatient and inpatient cases in Northern Ireland, more than half of patients are waiting over 52 weeks for treatment.35

It is important to note that waiting times for gynaecology are concerning across all of the Health and Social Care Trusts (HSCTs) in Northern Ireland, but the South Eastern HSCT has both the highest number of waiting times and the highest number of patients waiting for treatment per 100,000 of the population. Once again, the data we currently have available cannot explain the reasons behind this, but funding available to meet the needs of the population in Northern Ireland has been a challenge.36

The data available shows that women and people living in the areas of highest deprivation across the UK typically experience the longest waits for gynaecology care.37

This is indicative of wider research – as The Kings Fund reflected, the people most in need of care are often the ones who struggle the most to access services, ‘a longstanding injustice further entrenched by the COVID-19 pandemic and cost of living crisis’.38

To produce this report, we have used NHS official datasets that are available publicly, but this only tells part of the story.

The journey for women to reach the point of being referred for definitive treatment is long, but the data does not tell us where in the pathway women are being delayed the most, or how many women are in fact waiting for more than one type of definitive treatment.

We do know however that there are challenges with access to diagnostic tests and scans and this can lead to delayed diagnosis, misdiagnosis or cause complications when diagnostic scans are out of date by the time women reach surgery.

Whilst it is possible to calculate which patient groups often wait the longest, this data is not easily accessible, and data is not easily disaggregated. Far more data is needed to understand the link with health inequalities fully.

There is also no data accessible that shows where patients are being referred from, which could enable us to understand why some commissioners and providers across the UK are seeing sharp increases in demand and help to highlight the gaps in the provision of specialist gynaecology services to support operational planning.

Given the rising numbers of women waiting and the lengthening gynaecology waiting times, the RCOG designed a UK-wide survey and hosted a series of focus groups to understand in greater depth how waiting for gynaecology treatment continues to impact people’s lives.

Impact on physical health

When the RCOG wrote Left for too long, women told us that their symptoms had worsened whilst waiting for treatment.

This was again clear in our recent research, with more than six in ten women reflecting that their physical symptoms have worsened. Women’s symptoms continue to be extensive, debilitating and often change or fluctuate, making them very difficult to manage.

Many women mentioned intense pain and discomfort as a result of their gynaecological conditions and symptoms. Exhaustion, breathlessness, dizziness, anaemia and extensive blood loss as well as incontinence, difficulty walking, pelvic infections and flooding were commonly experienced. Women talked about regularly bleeding through their clothes, needing to be in close proximity to a toilet, feeling isolated and being unable to carry out their ‘normal’ lives due to physical pain.

Worsening chronic physical symptoms are at the heart of how women’s gynaecological conditions and symptoms are impacting other areas of their lives. This is indicative of wider research that shows that chronic pain can negatively impact multiple aspects of patient health, from sleep and cognitive processes to mental health, ability to have sex and overall quality of life.39

A quarter of women told us that they had needed to attend A&E or an emergency department as a result of their symptoms. Significantly, 11% of those respondents had gone on to have an emergency intervention, suggesting that women are suffering with such severe symptoms that they have reached the point of requiring emergency care. The increasing volume of emergency interventions is also a concern raised by clinicians, which we explore later in the report.

Naomi's story

Naomi lives in Suffolk and has experienced heavy painful periods for the past 10-12 years of her life.

Even after ultrasound investigations in 2013 and 2015, her symptoms were dismissed as ‘normal’.

In January this year, after waiting years for scans, Naomi was diagnosed with adenomyosis. After her formal diagnosis earlier this year, Naomi’s symptoms significantly worsened, and she experienced severe swelling and pain in her stomach that spread to under her ribs, making it increasingly harder to breathe.

Naomi was forced to go to A&E on several occasions, sometimes waiting over 30 hours to be seen. She was also admitted to hospital for five to six days, but each time sent home with strong pain medication to manage the pain herself. Naomi also tried hormonal contraception to improve her condition, but found that this exacerbated her depression and anxiety. Naomi felt forced to pay for private surgery, during which surgeons found that she also had deep infiltrating endometriosis which was on her kidneys.

Ana's story

Ana lives in London, and six years ago she was diagnosed with uterine fibroids.

Ana’s symptoms have been severe and have led to very heavy bleeding which can soak through products and clothes in seconds.

This means she often finds being outside her home very stressful and says no to certain events due to the fear that she might bleed. The blood loss and associated anaemia can leave her feeling exhausted and irritable which impacts her mental health and physical health.

In January 2023, Ana had an appointment with a gynaecologist and it was decided that her fibroid was too small to operate on, but her symptoms were gradually getting worse. Ana pushed for another appointment and had to wait almost a year to see a consultant. By this time, her fibroid had grown and she was finally booked in for surgery, but it was postponed.

During this time, Ana started becoming very anaemic due to the large volume of blood she was losing each month and was forced to get an iron infusion. Her iron levels were still low at the time of her planned operation, and it was advised they wouldn’t be able to operate as planned, but Ana fought against this and had her operation in June 2024.

Impact on mental health

It is widely understood that chronic long-term physical pain can also impact a person’s mental health.40

Over three quarters (76%) of the women and people we surveyed this year said their mental health had worsened whilst waiting for treatment, with many experiencing depression, anxiety and extreme worry.

Many mentioned their physical pain and other symptoms in this context, and some even said that the impact on their mental health had been so severe, that they had felt suicidal whilst waiting for treatment.

Amanda's story

Amanda lives in Essex and her life has been significantly impacted by waiting for gynaecology care.

She has struggled with medical trauma, and finds it increasingly difficult to go to her GP or to A&E after spending so much time in difficult medical appointments, or fighting to be taken seriously.

She has also struggled with her mental health because of her condition and finds herself socially isolated as she can’t often leave the house. “I’ve found myself in crisis before with suicidal thoughts and urges,” she told us.

Almost seven in ten women (68%) said their relationships or sex life had been negatively impacted whilst being on a waiting list.

The impact of physical symptoms often made sex ‘impossible’ and women said that they or their partners felt fearful of having sex, often because they were worried about the impact, such as infections or their symptoms flaring. This, alongside exhaustion, also caused a lack of libido or interest in sex.

Many women told us that waiting for treatment had resulted in relationship tensions and decline or left them feeling unable to have or pursue relationships at all. Waiting for vital treatment had also impacted many women’s plans to start a family because the risks were too high. As one respondent said, even though they wanted to start a family it just ‘isn’t possible’ until their fibroids are removed.

Issues with sex, intimacy, relationships and fertility often have detrimental impacts to mental health and wellbeing,41 and this was also evident in our research. As one woman told us, “I mourn my previous life.”

Nearly seven in ten of the women we surveyed in 2024 told us their ability to take part in work and social activities had been negatively impacted by their gynaecological condition.

They spoke of being housebound and regularly needing to cancel plans with friends or family due to debilitating and unpredictable symptoms, with many fearing bleeding or flooding without having access to a toilet. Some women told us they often felt embarrassed by their symptoms, and most women said they were not able to do many of the things they enjoyed in life, including exercise and hobbies, leaving them withdrawn and isolated.

Some women told us their condition and worsening symptoms had even impacted their school and education attendance, preventing them from accessing opportunities that would support their future.

Women told us they had needed to take increased sickness absence from their paid employment because of their condition and symptoms. Some women said they had felt forced to change careers, reduce their hours or leave their job completely due to the debilitating impact of their condition. For some respondents, the effect of their condition on their ability to work had caused a direct financial impact on their lives and they were fearful of the future.

Some women said they struggled to work their full-time hours but that they were either already struggling financially or concerned about whether they could afford to reduce their hours despite feeling deeply unwell. As one woman told us, if she had been single, she would have been ‘financially destitute and homeless’.

Whilst some women discussed that adjustments had been put in place at their workplace, many had not received any support from their employers. Our research shows that many women are giving all their energy to stay at work but have sacrificed their social life and health to do so, with many spending their free time outside of work recovering.

The impact of these prolonged waits for gynaecology treatment affects society as a whole and should concern all of us. A comprehensive body of secondary research demonstrates the extensive and essential role women play in the economy, both nationally and globally.

Women make up a significant portion of the UK workforce in key sectors, including health and social care, education, and the civil service.42 As of early 2022, there were 15.61 million women over 16 in employment in the UK,43 and women-owned businesses contributed approximately £105 billion to the UK economy.44

The Fawcett Society estimates that the UK is losing 150 million working days each year due to women's poor health and a lack of suitable support.45 It is simply unacceptable that women are having to work less, or being forced out of work altogether, because their gynaecological health needs are not being met.

Women also tend to be paid less46 and undertake more unpaid work than men, which often goes unrecognised. Health Equity North’s Women of the North report found that women living in the north of England contribute £10 billion of unpaid care to the UK economy each year, £2 billion higher than the national average, and work more hours for less pay.47 Again, this shows why it is vitally important to society as a whole that women have access to the healthcare they need to support themselves, their families and communities.

Added to this, women are often the main ‘shock absorbers of poverty’, because women tend to have more responsibility for the purchase and management of food and household finances.48 Some schemes provide access to free period products in England and Wales49 50, and the Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Assembly passed legislation to enable access free period products within certain public services.51

However, the majority of women continue to have to cover the cost of addressing their symptoms, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and pain management. Given that those living in areas of deprivation often wait the longest for treatment, this financial burden is another compounding issue and one that is likely to be perpetuating inequalities.52 Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On emphasised that growing inequalities are harming ‘individuals, families, communities and are expensive to the public purse,’ yet are ‘unnecessary and can be reduced with the right policies.’53

Continued underinvestment in women’s health, and gynaecology care in particular, is not only deeply unfair, but will have a catastrophic impact on individuals, families and on local and national economies if it is not resolved. It is also a missed opportunity, as the NHS Confederation’s recent report shows, for every additional £1 of public investment in obstetrics and gynaecology services per woman in England, there is an estimated return of investment of £11.54

Elizabeth's story

Elizabeth lives in the Midlands, and four and half years ago, she started to struggle with colorectal symptoms, finding it very difficult to empty her bowels and had constant pain.

She was struggling to walk and was finding no relief for her symptoms. Elizabeth was eventually diagnosed with a rectocele, which means that her bowel had collapsed into the vagina and is a type of prolapse.

Elizabeth needed major surgery, and whilst waiting for surgery, her symptoms were getting progressively more intrusive and she started to experience urinary incontinence, leaving her housebound most of the time. Elizabeth had to give up her work and explained the financial toll this took on her life savings, coupled with funding private appointments.

Elizabeth explained the constant state of anxiety and stress she feels and the impact this has had on her wider relationships with family and friends. She is unable do everyday activities that used to bring her joy like gardening or riding a bike. “I don’t think people have a grasp of how painful these conditions are,” Elizabeth told us. “How can I continue my life as normal when I can’t stand or sit due to the pain?”

Kate's story

Kate is 35 and lives in London with her partner and works full time as a busy senior manager. Kate was diagnosed with endometriosis in 2023 and discovered she had three large cysts on her ovaries.

Kate had surgery to remove the cysts and needed to take a lot of time off work to recover. Since her surgery, Kate started experiencing pain again and a second ultrasound revealed that she has a new cyst. Kate was promoted to a new senior role before her first surgery due to hard work across her career.

However, Kate felt frustrated by her symptoms and guilty for taking time off work when things were particularly bad. “It has made me doubt myself and my ability to do a job that I know I’m good at because I can’t give 100% to it whilst I’m in so much pain,” Kate told us.

Support, information and guidance

Our research demonstrates that waiting times have resulted in increasingly complex conditions and care needs. However, despite the high need for support, most women told us they could not access the support they needed.

Nine in ten women we surveyed this year said they had not been offered any support from the hospital to help manage their symptoms, leading many to seek support in primary care. Almost three quarters of women (73%) told us they had sought additional help in primary care in relation to their gynaecological health or symptoms, with 62% of women saying they had needed to return to their GP over three times.

Some women mentioned that they had positive experiences, especially with individual GPs, but most women told us that their appointments and communication touchpoints along their care journey were not meeting their needs. They described the support they receive as inaccessible, limited, and they are often ‘timing out’ of accessing it.

Some women are turning to online communities instead, and whilst many praised these resources, most reflected disappointment at the lack of information, guidance and support from the system. Logistics around their care, information about conditions and symptoms, what to expect and how to prepare for appointments were key areas where women wished they had been provided with information.

Women said that alongside a lack of general guidance, they feel support is often not tailored to their personal needs or circumstances, limiting their options and ability to make informed choices. Our Women’s Network expert members told us that women reported being advised by professionals that was not suitable or did not address the root causes of their symptoms. This included being advised to lose weight and exercise, despite being unable to exercise due to debilitating pain.

Many women said that due to a lack of education and access to information and support, their journey to understanding their condition was incredibly difficult. Many reflected that there is still a lot of stigma and myth around gynaecological care and that more education is needed, not just for women, but for younger girls and more broadly across all areas of society.

They see this lack of awareness and understanding as intensifying the impact of their condition on other areas of their life, for example, in their social and work lives. Many women reflected on how important it is for workplaces to be aware of their conditions to enable better access to support and adjustments.

Access to specialist support, such as pelvic health physiotherapy, was also raised as a key issue. Some women specifically noted the difference in the provision of specialist support for other conditions, such as cancer.

For example, in cancer, there are often multidisciplinary teams available and cancer nurse specialists who can support proactive case management, provide psychological support, and provide specialist symptom control. As one participant reflected, this would ‘improve continuity of care, knowing you have someone you can just contact’.

Grace's story

“I feel like gynaecological conditions are really stigmatised and lots of the blame has been shifted back onto me to make changes in my lifestyle”, Grace explained.

Grace is a healthy and very active person who has often found her concerns and symptoms have been brushed aside, and therefore feels reluctant to keep trying to access care based on these previous experiences.

As a mixed-race woman, Grace feels as though the intersection between her race and gender has left her particularly powerless to advocate for herself and have her condition taken seriously. Grace explained that access to support like pelvic floor physiotherapy, nurse-led pain clinics and mental health support would be invaluable in helping women who are waiting for care to manage their symptoms.

Self-advocacy and patient initiated follow up

Many women told us they found interacting with the health system exhausting, often feeling alone in managing the progress of their care.

We asked women and people waiting to describe their feelings about patient-initiated follow-up (PIFU), a policy in England where the patient initiates an appointment when they need one, based on their symptoms and individual circumstances.55

Those surveyed had mixed views on the benefits of this policy, with over 60% either disagreeing or strongly disagreeing when asked if they felt confident they could manage their gynaecological symptoms whilst on the waiting list. Scepticism was based on the current reality: as it stands, women cannot easily access professional follow up, even if they are initiating that follow up.

Many also challenged that without medical expertise, the onus should not be on patients to decide when follow-up to complex conditions or symptoms is necessary. Concern was also expressed that PIFU could even exacerbate inequalities, given it is predicated on those who are waiting to have the capacity, ability and health literacy to be proactive about their care. For PIFU to work, women said that it would have to be accessible and guarantee a timely follow up.

Women told us that communication around their care was often poor, with only one in 10 women saying that the communication they had received had been good.

Whilst women had differing views on what communication would work best for them, it was clear that what, how and when things were communicated to patients was not working.

Methods of communication varied hugely, communication could be unclear or confusing, and the regularity of communication was not proactive or sufficient. Together, this compounded women’s anxiety, leaving many desperately chasing professionals for updates or clarity.

Women discussed how difficult it was to navigate the system and that it was unclear who was responsible for their care. Conflicting advice from professionals and a lack of transparency about how long they would be waiting left many women distressed but also desperate to speak to the same person and have one point of contact.

Some women raised that poor communication had also caused issues with consent, feeling that specific options or choices were pushed on them rather than being discussed or had been missing in key moments in the process. This raises significant questions about how effective PIFU could be unless these fundamental issues with communication are resolved across the system.

Whilst some women did mention positive experiences with individual healthcare professionals, a considerable number of women told us they felt they had not been listened to, believed or taken seriously when they had come forward to seek help. Some women said that language had been harmful, for example, when professionals responded that there was ‘nothing of concern’ when they had reported pain.

Speaking to healthcare professionals had felt ‘like an interrogation’ at times for some women, with many feeling they had to ‘prove’ that their symptoms were as extreme as they had disclosed. What often compounded this stress was that many women felt their healthcare professionals, particularly those in primary care, were, in effect, the gatekeepers of being able to access further care.

Better communication, including:

- Transparency, honesty and consistency of messaging on how long they might expect to wait.

- Accessible, regular and proactive communication, including updates about referrals being processed.

- Clarity on who is responsible for their care along their journey.

Easier access to advice and information, and flexible and specialist follow up care, including:

- More regular and accessible follow up opportunities and not ‘timing out’ on follow up appointments, given symptoms and conditions are long term and can change.

- Better guidance on what to expect from appointments and their pathway journey, how to prepare best for appointments, symptoms and wider sources of support they can access.

- Better and more equitable access to important specialists in women’s health and specific areas, including group sessions.

Feeling believed and listened to from the very first appointment, and always.

Breaking the taboo and creating greater awareness and education about gynaecological conditions and symptoms across society.

In the development of this report, the College sought the views of professionals working across all parts of the gynaecology care and treatment pathway, to understand their experiences and what they perceived as the barriers and enablers to addressing gynaecology waiting lists.

The RCOG convened an Expert Clinical Research Group of professionals working in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, we surveyed professionals working across the UK in secondary care settings and we hosted a series of follow-up focus groups to more deeply understand their experiences.

We also worked with the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) to survey primary care professionals across the UK.

The most powerful message from professionals working across both primary and secondary care was the serious concern they had for their patients and the impact that the long wait for definitive treatment in secondary care was having on their patients' health and wellbeing.

They told us they were seeing severe symptoms, such as heavy bleeding, clotting, acute pelvic pain, and increasing numbers of women needing emergency care, with 80% of secondary care professionals reporting a significant or mild increase in emergency admissions.

Many said women were also facing unacceptably long waits in emergency departments waiting to be seen. Professionals also raised concerns about wider health outcomes being impacted as a result of worsening symptoms and poorer quality of life.

For example, patients may be at greater risk of life-threatening conditions, such as heart disease or pulmonary embolism, because symptoms such as pain and iron deficiency are so debilitating they prevent women from enjoying a healthy lifestyle.

In Left for too Long in 2022, the RCOG warned that long waits for gynaecology treatment presented risks, such as disease progression.56

In our new research, it is evident that increasing waiting times are resulting in disease progression and an increase in complexity of conditions and symptoms, like growing fibroids, worsening endometriosis and worsening prolapses.

80% of primary care professionals in our survey told us they were seeing patients with more complex care and treatment needs, and secondary care professionals emphasised this too, particularly the increasing pressure on emergency gynaecology teams and units.

Unsurprisingly, the impact of demand and complexity of workload was clear, with both professionals in secondary and primary care reporting that the impact of gynaecology lists on their workload is significant.

Professionals in both primary and secondary care told us that it is difficult to support women whilst they are waiting, especially in complex cases. Symptom management options in primary care are quickly exhausted, and in secondary care, women are often desperate to have urgent surgery, which is not possible given capacity and complexity. Professionals emphasised the importance of having the time and ability to access training to support women with complex conditions and symptoms, to ensure quality and safe care.

It is understandable that seeing increasing numbers of women in distress is leaving professionals feeling burned out. Seven out of ten professionals in secondary care and over six out of ten professionals in primary care reported an impact on their own health and wellbeing, or that of their colleagues.

Many told us that they are seeing a growing number of anxious patients, but feel ‘helpless’ that they have no power to expedite waiting lists. For primary care professionals particularly, they reported that often being the first or regular point of contact for women in distress is particularly challenging.

Fundamentally, staff are feeling the negative impact on their wellbeing of not being able to deliver a quality service with many discussing the moral injury they experience at seeing their patients in distress, without the resources to help them.

Growing gynaecology lists and fewer staff available is exacerbating pressure on all parts of the service, with many professionals mentioning an increase in staff sickness as a result, often for stress-related reasons.

Many feel guilty for taking time off, even when it has been recommended by their own healthcare professional, and some described colleagues leaving the profession altogether or taking early retirement because they felt ‘too responsible’ day in day out for the impact of the long waits on their patients.

These results are evident in national NHS workforce surveys, and professionals warned that given the context of staff burnout, gynaecology waiting list initiatives must be planned sustainably and in a way that protects staff wellbeing.

As the data in Section One of this report reveals, it is clear that demand currently outstrips capacity in hospital gynaecology services.

There has been a steady increase in referrals over recent years, as well as mounting pressures on other parts of gynaecology services, for example, the growing number of referrals for post-menopausal bleeding as a result of an increase in the uptake of Hormone Replacement Therapy.57

Through the College’s research to inform this report, healthcare professionals from across the UK outlined how funding is a fundamental barrier to addressing staffing levels. This includes:

- Inadequate national funding – Healthcare professionals emphasised that funding levels had not enabled sustainable investment in essential resources, such as NHS estates, equipment and digital infrastructure.

- The challenges of short-term national funding decisions in recent years – Healthcare professionals told us this had resulted in an overreliance on temporary capacity, such as locum or bank staff. This means Specialty, Associate Specialist and Specialist doctors face barriers to career progression, and Locally Employed Doctors who make up a growing part of the gynaecology workforce could not then be offered permanent contracts.

- Financial incentives and commissioning of services — Healthcare professionals discussed the impact of financial incentives and commissioning arrangements, such as the NHS tariff scheme and that funding is often prioritised for consultant-led elective care. These policies set at a national level can create barriers to establishing multi-professional working and delivering care outside of elective settings.

- The lack of prioritisation of gynaecology as a specialty – This perpetuates funding challenges, with professionals often left with the burden of producing business cases, for example to secure funding for specialists to train their generalist colleagues or to expand access to early interventions (e.g. physiotherapy, pessary fittings and uro-dynamics). Despite these initiatives having the potential to support workforce capacity in the longer term, prevent disease progression in patients and decrease surgical demand, business cases are often rejected against other operational priorities.

Together, these challenges hinder longer term operational planning and limit systems in delivering against national targets by creating inefficiencies and unnecessary barriers to transformation and innovation.

Alongside funding restrictions, staffing levels have not increased to meet the growing demand across the UK. This was raised consistently as a challenge by professionals, both from a wellbeing and delivery perspective.

Analysis by the RCGP demonstrates that the average individual GP is now responsible for 2,294 patients, a 7.2% increase on pre-pandemic levels.58 However, the number of fully qualified GPs (including locums) has been steadily declining, with 1.9% fewer fully qualified full time equivalent GPs compared to pre-pandemic levels.59

Primary care professionals told us they had less time to discuss what patients needed and that the administrative burden had increased substantially, for example, chasing referrals to secondary care or taking action to find advice to resolve complex care. This is against a backdrop of delivering more appointments and managing demand across other conditions.

Secondary care professionals acknowledged the pressures on other parts of the system, including for colleagues in primary care and mental health professionals, who are now having to support patients for longer whilst they wait for treatment in secondary care. In secondary care, professionals said there are specific gynaecology sub-specialities that are particularly challenged, such as complex endometriosis surgery and urogynaecology. This is driven by a range of reasons, including:

- Problems with diagnostic imaging and scans – Access to timely scans and the professional competency in the system to interpret scans correctly is a common challenge. This often results in cancelled surgeries because scans are out of date by the time the woman reaches surgery.

- Complexity of surgeries caused by disease progression due to long waiting times – This results in increased demand on theatre capacity and professional time.

- Increasing pressures on A&E – Workforce capacity, including capacity of trainees, is often required to deliver emergency gynaecology. This leaves less capacity for planned elective care or delivering initiatives to tackle the backlog, such as additional clinics, perpetuating the backlog cycle.

- Theatre capacity and wider elective pressures – As gynaecology surgeries are more complex, incentives and pressures to deliver against elective targets often mean space is prioritised for shorter and less complex surgeries.

- Limited access to professionals with the right skill set or sub-specialist skills – only British Society for Gynaecology Endoscopy (BSGE) accredited centres can manage severe or deep-infiltrating endometriosis, and additional specialist surgeons are often required for complex endometriosis, making scheduling even more difficult.

- The higher prevalence of co-morbidities – for example, conditions such as procidentia, a severe form of organ prolapse, or sepsis as a result of prolapse complications – makes delivering safe care more complex. This includes anaesthesia, gynaecology, and urogynaecology.

It is important to note that the staffing problems reported by healthcare professionals vary across professions and across regions and providers. However, whilst the impact of the pandemic on gynaecology care cannot be understated, it is the continued deprioritisation in wider elective recovery and the lack of system resources which continues to compound the crisis.

Poor communication between primary and secondary care professionals was also raised as a key barrier to delivering better care for women.

Primary care professionals said that they are sometimes not sure if patient referrals have been accepted and they often lack additional support around referral guidance or the pathways for gynaecology care.

Many told us that reaching secondary care colleagues is exceedingly difficult, and they have to manage the expectations of patients which might have been set in secondary care, often due to a lack of understanding of what primary care could provide.

Secondary care professionals understand that their primary care colleagues do not always have the expertise to manage more complex cases and reported that they struggle to find time to dedicate to supporting primary care clinicians.

They also feel that there is poor communication or misalignment between clinical staff and operational managers, underlining the workforce culture issues that have been documented in wider national inquiries and reports.60 Both primary and secondary care professionals said that additional support for women in the community (e.g. via Women’s Health Hubs) is not available in all parts of the UK.

Funding and capacity, alongside the lack of priority given to gynaecology, are at the heart of training and education issues.

Nurses told us that the lack of clarity around professional roles in gynaecology, such as specialist and Advanced Nurse Practitioner roles, result in fewer higher education settings offering the appropriate courses. Nurses also told us that higher education courses often provide training on specific portfolios like cancer, but the pathway to specialising in gynaecology is unclear and less accessible.

Trainees working in secondary care reported their practical training often gives predominant focus to obstetrics, which means they cannot devote the time required to develop the competencies to deliver safe gynaecology care. Trainees are disappointed that it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to access training for essential core skills to deliver gynaecology care, such as performing and interpreting scans and pelvic ultrasounds or training in outpatient gynaecology care settings.

Many senior professionals explained how they are not given adequate time to maintain the level of skill required to ensure high-quality care and safety for their patients and also to train newer professionals. In addition, senior professionals mentioned that increasingly complex procedures are sometimes not appropriate for training purposes, impacting training opportunities further. Similarly, primary care professionals emphasised that their capacity was limited, leaving them little time to upskill not only in gynaecology care, but across other conditions.

In the Left for too long report we suggested the Government could consider private sector capacity to tackle gynaecology waiting lists. However, in our recent research, professionals told us that the increase of surgery being delivered outside standard NHS settings had resulted in fewer opportunities for obstetrics and gynaecology trainees to gain the skills and competencies they need in gynaecology surgery. Overreliance on private sector capacity therefore risks perpetuating existing gynaecology workforce issues and so its deployment must be considered carefully.

As the data in Section One of this report reveals, it is clear that demand currently outstrips capacity in hospital gynaecology services.

There has been a steady increase in referrals over recent years, as well as mounting pressures on other parts of gynaecology services, for example, the growing number of referrals for post-menopausal bleeding as a result of an increase in the uptake of Hormone Replacement Therapy.57

Through the College’s research to inform this report, healthcare professionals from across the UK outlined how funding is a fundamental barrier to addressing staffing levels. This includes:

- Inadequate national funding – Healthcare professionals emphasised that funding levels had not enabled sustainable investment in essential resources, such as NHS estates, equipment and digital infrastructure.

- The challenges of short-term national funding decisions in recent years – Healthcare professionals told us this had resulted in an overreliance on temporary capacity, such as locum or bank staff. This means Specialty, Associate Specialist and Specialist doctors face barriers to career progression, and Locally Employed Doctors who make up a growing part of the gynaecology workforce could not then be offered permanent contracts.

- Financial incentives and commissioning of services — Healthcare professionals discussed the impact of financial incentives and commissioning arrangements, such as the NHS tariff scheme and that funding is often prioritised for consultant-led elective care. These policies set at a national level can create barriers to establishing multi-professional working and delivering care outside of elective settings.

- The lack of prioritisation of gynaecology as a specialty – This perpetuates funding challenges, with professionals often left with the burden of producing business cases, for example to secure funding for specialists to train their generalist colleagues or to expand access to early interventions (e.g. physiotherapy, pessary fittings and uro-dynamics). Despite these initiatives having the potential to support workforce capacity in the longer term, prevent disease progression in patients and decrease surgical demand, business cases are often rejected against other operational priorities.

Together, these challenges hinder longer term operational planning and limit systems in delivering against national targets by creating inefficiencies and unnecessary barriers to transformation and innovation.

Alongside funding restrictions, staffing levels have not increased to meet the growing demand across the UK. This was raised consistently as a challenge by professionals, both from a wellbeing and delivery perspective.

Analysis by the RCGP demonstrates that the average individual GP is now responsible for 2,294 patients, a 7.2% increase on pre-pandemic levels.58 However, the number of fully qualified GPs (including locums) has been steadily declining, with 1.9% fewer fully qualified full time equivalent GPs compared to pre-pandemic levels.59

Primary care professionals told us they had less time to discuss what patients needed and that the administrative burden had increased substantially, for example, chasing referrals to secondary care or taking action to find advice to resolve complex care. This is against a backdrop of delivering more appointments and managing demand across other conditions.

Secondary care professionals acknowledged the pressures on other parts of the system, including for colleagues in primary care and mental health professionals, who are now having to support patients for longer whilst they wait for treatment in secondary care. In secondary care, professionals said there are specific gynaecology sub-specialities that are particularly challenged, such as complex endometriosis surgery and urogynaecology. This is driven by a range of reasons, including:

- Problems with diagnostic imaging and scans – Access to timely scans and the professional competency in the system to interpret scans correctly is a common challenge. This often results in cancelled surgeries because scans are out of date by the time the woman reaches surgery.

- Complexity of surgeries caused by disease progression due to long waiting times – This results in increased demand on theatre capacity and professional time.

- Increasing pressures on A&E – Workforce capacity, including capacity of trainees, is often required to deliver emergency gynaecology. This leaves less capacity for planned elective care or delivering initiatives to tackle the backlog, such as additional clinics, perpetuating the backlog cycle.

- Theatre capacity and wider elective pressures – As gynaecology surgeries are more complex, incentives and pressures to deliver against elective targets often mean space is prioritised for shorter and less complex surgeries.

- Limited access to professionals with the right skill set or sub-specialist skills – only British Society for Gynaecology Endoscopy (BSGE) accredited centres can manage severe or deep-infiltrating endometriosis, and additional specialist surgeons are often required for complex endometriosis, making scheduling even more difficult.

- The higher prevalence of co-morbidities – for example, conditions such as procidentia, a severe form of organ prolapse, or sepsis as a result of prolapse complications – makes delivering safe care more complex. This includes anaesthesia, gynaecology, and urogynaecology.

It is important to note that the staffing problems reported by healthcare professionals vary across professions and across regions and providers. However, whilst the impact of the pandemic on gynaecology care cannot be understated, it is the continued deprioritisation in wider elective recovery and the lack of system resources which continues to compound the crisis.

Poor communication between primary and secondary care professionals was also raised as a key barrier to delivering better care for women.

Primary care professionals said that they are sometimes not sure if patient referrals have been accepted and they often lack additional support around referral guidance or the pathways for gynaecology care.

Many told us that reaching secondary care colleagues is exceedingly difficult, and they have to manage the expectations of patients which might have been set in secondary care, often due to a lack of understanding of what primary care could provide.

Secondary care professionals understand that their primary care colleagues do not always have the expertise to manage more complex cases and reported that they struggle to find time to dedicate to supporting primary care clinicians.

They also feel that there is poor communication or misalignment between clinical staff and operational managers, underlining the workforce culture issues that have been documented in wider national inquiries and reports.60 Both primary and secondary care professionals said that additional support for women in the community (e.g. via Women’s Health Hubs) is not available in all parts of the UK.

Funding and capacity, alongside the lack of priority given to gynaecology, are at the heart of training and education issues.

Nurses told us that the lack of clarity around professional roles in gynaecology, such as specialist and Advanced Nurse Practitioner roles, result in fewer higher education settings offering the appropriate courses. Nurses also told us that higher education courses often provide training on specific portfolios like cancer, but the pathway to specialising in gynaecology is unclear and less accessible.

Trainees working in secondary care reported their practical training often gives predominant focus to obstetrics, which means they cannot devote the time required to develop the competencies to deliver safe gynaecology care. Trainees are disappointed that it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to access training for essential core skills to deliver gynaecology care, such as performing and interpreting scans and pelvic ultrasounds or training in outpatient gynaecology care settings.

Many senior professionals explained how they are not given adequate time to maintain the level of skill required to ensure high-quality care and safety for their patients and also to train newer professionals. In addition, senior professionals mentioned that increasingly complex procedures are sometimes not appropriate for training purposes, impacting training opportunities further. Similarly, primary care professionals emphasised that their capacity was limited, leaving them little time to upskill not only in gynaecology care, but across other conditions.

In the Left for too long report we suggested the Government could consider private sector capacity to tackle gynaecology waiting lists. However, in our recent research, professionals told us that the increase of surgery being delivered outside standard NHS settings had resulted in fewer opportunities for obstetrics and gynaecology trainees to gain the skills and competencies they need in gynaecology surgery. Overreliance on private sector capacity therefore risks perpetuating existing gynaecology workforce issues and so its deployment must be considered carefully.

For all professionals:

Adequate funding, for both primary and secondary care, to create the necessary capacity in gynaecology services to deliver high quality care for women and start to bring down waiting times.

For professionals in primary care:

Better communication between primary and secondary care, including easier access to advice across the pathway.

Clearer and more transparent communication between providers and patients, particularly on how long the wait might be.

Better understanding among colleagues and patients of what primary care can and cannot provide.

Comprehensive commissioning of services in community settings, for example in Women’s Health Hubs or specific clinics, with secondary care colleagues providing specialist expertise.

Opportunities for primary care professionals to train and develop specialist skills, and to learn from secondary care clinicians who are specialists in gynaecology or women’s health.

For professionals in secondary care:

Funding for estates and infrastructure, including digital infrastructure, equipment and beds.

Priority given to theatre space for gynaecology across the NHS as part of elective recovery plans.

Time, capacity and funding to establish multi-professional working to improve culture and build awareness across the pathway.

Protected time to train for all roles and levels in secondary care, to ensure competence and experience.

Better access to specialist education for gynaecology, from university courses to continued professional development programmes.

Professionals across gynaecology care and treatment pathways continue to drive initiatives to improve patient experiences in gynaecology care.61

The national Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) programme in England, which includes gynaecology, is undertaking work to improve gynaecology pathways and service users’ experiences of, and access to, care.62 However, compared to other specialities like cancer, where clear patient pathways and national targets are already established, the work in gynaecology is still in early development.

There is national level guidance for providers on communication with people waiting for care in England, Scotland and Wales,63 and general information on health and wellbeing as part of platforms like My Planned Care in England or Waiting Well in Scotland.64

However, there is no way of measuring patient satisfaction or consistent implementation of guidance, and the gap in the provision of relevant information and support for women waiting was clear in our research.

Local and online support groups and charities are often invaluable to women,65 providing emotional support, helpful resources and digital tools as well as raising awareness of women’s health needs through advocacy and research work.66

However, as emphasised in Section Two, women frequently sought out these forums as a result of having inadequate support from health services. Support also should not replace timely access to medical care: ‘there is a time and place for peer support and time for medical support.’67

The College has advocated for Women’s Health Hubs for several years,68 and we welcomed the funding commitment of £25 million in 2023 so that each Integrated Care Board (ICB) in England could establish or expand a hub by the end of December 2024.69

Early evaluations of hubs are promising,70 and in our research, professionals said hubs had helped to establish multi-professional team working, improve training opportunities, make efficient use of clinical time and deliver more personalised support to women. However, there is variation in the maturity of hubs across England, and it is unclear if the target to establish a hub in every ICB by the end of December 2024 will be met.71

In addition, the funding for hubs is only committed to 2025. As the study from the Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge (BRACE) rapid evaluation centre concluded, sustained funding is essential to scale up hubs, and if they are not scaled up equally, there is a risk hubs could widen inequalities if they are more accessible to advantaged groups.72

Case study: A longstanding women's health hub in Birmingham

Launched in 2016, Modality gynaecology service in Birmingham is now an extensive women’s health hub providing a range of gynaecology services to women across the Midlands. Following GP referral, women can access diagnostic tests, consultation and treatment for a range of women's health conditions. The hub:

• delivers training opportunities for professionals,

• reduces unnecessary referrals, with less than 10% onward referral rate to secondary care and;

• enables women to access support quickly, delivering up to 1,000 appointments each month.

Dr Aamena Salar, a GP specialising in women’s health, founded the service. Reflecting on its development, Dr Salar noted helpful shifts in approaches to commissioning over the past ten years, but the transformation ultimately needed sustained capacity, time and investment.

Professionals shared a range of local approaches that have been piloted to tackle waiting lists across the UK. This included running additional clinics and working to validate waiting lists with administrative teams and clinicians to prevent duplication, ensure women have been referred to the correct pathway and identify those with worsening symptoms.

However, there was significant variation in the capacity available to deliver initiatives, and clinicians explained that validation of lists was often not included in their job plans. Payment issues, staff availability and burnout were also core challenges to delivery. There are also practical limitations, such as the cost of travelling to alternative providers, that can prevent some women taking up offers as part of local or national backlog schemes (such as the NHS Choice Framework in England).73

Whilst there are promising instances of best practice, progress is hindered by a lack of prioritisation and investment in gynaecology. There is often a lack of resource to scale up best practice, with services reliant on professionals with a special interest in women’s health and those who are willing to deliver additional work outside of core funded hours.