Eddie Morris, RCOG President

Ahead of my election as RCOG president in 2019, I spent much time deciding what my priorities would be if I were to be elected. But one priority was always clear to me – the need to reverse the growth of NHS waiting lists in gynaecology, and to ensure that women can access high-quality, timely care and treatment. With the impact of the pandemic, this priority has only gained in both importance and urgency, and I hope this report will help facilitate much-needed action.

This publication confirms the experience of myself and many of my colleagues working in gynaecology; that waiting lists were growing too quickly before the pandemic hit, and the negative impact on many women waiting longer for care is significant. Often when I speak to women, I hear just a fraction of what they’ve managed to tolerate for months on end. There is often no part of their lives that is left unscathed by the impact of their gynaecological condition. For many, living with symptoms including extreme pain, heavy menstrual bleeding, and incontinence has become a part of who they are, and their suffering should not be ignored.

Alongside the data available, it was important to me that we heard directly from women about their experiences. It is their voices, thoughts, and experiences that this report highlights. It is their stories that we have an obligation to tell. It was also essential for me to hear from RCOG members on the ground, who are trying their best to deliver care during these difficult times without the resource they desperately need.

I would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this project in whichever way they have been able to. I am humbled by the courage shown by women who have openly shared their experiences and helped break down the unnecessary stigma that still shrouds these conditions. We are grateful for the confidence they have shown in the RCOG to drive change and we hope leaders and policy makers see clearly how real their plight is.

This report raises some difficult questions. Why it is that the waiting lists of the only specialty that caters just for women have grown the most of all specialties since the start of the pandemic? Why is there so little discussion or recognition of the impact on women’s lives of waiting for gynaecological care and treatment? And how much has the perception of many of these conditions as ‘benign’, simply because they do not pose a threat to life, played in to the lack of priority they have long been given? Do healthcare providers allocate proportionately fair amounts of capacity in environments such as operating theatres for women’s health?

There is one thing that this report makes clear, and that is that change is desperately needed. We are letting women and people with these conditions down badly, and action needs to be taken to make sure that gynaecology is given the attention it so desperately needs as the NHS recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, and doesn’t continue to be seen and treated as a second class speciality.

Shaista Gohir, RCOG’s Women’s Network Chair

Action is desperately needed, with this report showing gynaecology waiting lists growing for some time even before the COVID-19 pandemic. When there is pressure on the NHS, gynaecology services seem to bear the brunt of cuts. As the powerful accounts of women’s experiences show, conditions can be so painful and debilitating that they can impact on every aspect of family, social and work life. Delay in care also inevitably ends up costing women and the NHS in the long term – it is time to change how gynaecological health is viewed amongst decision makers at the highest levels.

Struggling to access the right care and support for many gynaecological conditions is not a new experience for women and is the result of a lack of investment and attention given to women’s healthcare historically. Through this new report the RCOG is shining a light on the true impact of gynaecology waiting lists on women and on the wider health system and calling for an NHS recovery that meets the needs of women on gynaecology waiting lists and finally gives parity to a speciality that has too often been overlooked.

Women are waiting longer than ever for their care. This report shows the stark growth of waiting lists in elective gynaecology across all four UK nations, with new analysis showing:

· Gynaecology waiting lists across the UK have now reached a combined figure of over 570,000 women across the UK – just over a 60% increase on pre-pandemic levels

· Gynaecology waiting lists in England have grown the most in percentage terms of all elective specialties

· The number of women waiting over a year for care in England has increased from 66 before the pandemic to nearly 25,000

By giving women the chance to tell their stories, this report outlines the significant impact of these longer waiting times on the progression of gynaecological conditions, the physical and mental health of the women, and on their quality of life – all evidenced by the experiences of both women and RCOG members. It also shows the huge geographic disparities in the length of waiting lists and highlights that the number of women needing care is potentially considerably higher than waiting lists suggest as a result of the lower number of referrals during the pandemic.

To fully meet the needs of women on waiting lists and ensure the effective and equitable recovery of elective gynaecology services the RCOG recommends:

1. Prioritisation of care as part of NHS recovery must look beyond clinical need to also consider the wider impacts on patients waiting for care.

2. There needs to be a shift in the way gynaecology is prioritised as a specialty across the health service, including action to move away from using the term ‘benign’ to describe gynaecological conditions.

3. Elective recovery must address the unequal growth of gynaecology waiting lists compared to other specialties.

4. Elective recovery in gynaecology must focus on reducing the disparities between different regions and CCGs, ending the postcode lottery for gynaecology care.

5. Governments across all four nations must put in place fully-funded, long-term plans for the NHS workforce to ensure that staffing does not continue to be a barrier to reducing waiting lists.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the introduction of the first national lockdown in March 2020, the NHS has been under constant pressure.

In early 2020, NHS bodies were told to postpone all non-urgent elective operations for a period of at least three months, with just emergency admissions, cancer treatment and other clinically urgent care to continue.i

Since the end of the first wave of the pandemic and the lifting of restrictions, the NHS has had to react quickly to re-direct capacity between recovery and delivery of care for COVID-19 patients, as new waves of the pandemic have arisen. The significant increases in COVID-19 cases and hospitalisations in the winter of 2020 put a stall on recovery and the reduction in waiting lists that had been achieved over the warmer months, though some units’ activities remained constrained for longer if they were deemed ‘surge centres’. The early months of 2021 saw high levels of hospitalisations caused by COVID-19 infections and much non-urgent care was again paused to ensure there was bed capacity to care for those with the most urgent clinical need, including the closure of theatres to provide additional space for ventilated patients with COVID-19.

In Obstetrics and Gynaecology (O&G), throughout the pandemic there has been a focus on ensuring maternity services were able to deliver safe care, protecting access to diagnosis and treatment for gynaecological cancers, and delivering acute gynaecological services to manage problems in early pregnancy (such as miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy) and other acute conditions. Redeployment affected staffing capacity in O&G during the first wave, as it did across the NHS, although joint calls by the RCOG and the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) led to limited redeployment outside of maternity services in subsequent waves, compared to other specialties.ii

A survey undertaken by the RCOG following the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic showed that approximately half (53%) of Trusts or units that responded had O&G consultants and Specialty and Associate Specialist (SAS) doctors redeployed to improve obstetric cover instead of working in gynaecology, with 50% of gynaecology consultants providing support in emergency obstetricsiii. Although it was absolutely necessary to ensure the safe delivery of maternity services throughout the pandemic and the RCOG supported the redeployment and, where necessary, the re-training of gynaecology doctors to work in maternity care, this has no doubt had an effect on capacity in elective gynaecology.

The total pausing of elective care at the start of the pandemic, as well as the ongoing impact of COVID-19 in hospitals that is continuing to hamper recovery, has resulted in the largest backlog in elective care the NHS has ever seen. Waiting list numbers across all specialties rose to almost six million at the end of 2021. The impact on staffing and capacity caused by the Omicron variant throughout the winter months is very likely to have worsened this national picture. The National Audit Office (NAO) has projected that elective care waiting lists will continue to grow to between seven and 12 million by March 2025, depending on the future growth of elective capacity.

Through this report, the RCOG aims to shine a light on gynaecology waiting lists, and to tell the stories of the women who are waiting longer than ever for their care. It is essential to understand waiting lists across the UK in more detail, and the changes that have taken place over the course of time and depending on where women live. The report also provides insight into the impact of waiting lists on individual women and their families, and considers the wider impacts on the health system and society as a whole. The report concludes by examining the challenge ahead to reduce the backlog in gynaecology, and considers what the solutions might be.

This report aims to be part of a wider conversation about NHS recovery and how the NHS works to reduce the backlog in elective care and deliver timely, high-quality care to everyone who needs it. The College wants to ensure that women’s voices are heard and their needs are considered as part of this conversation, and that gynaecology services and women’s health more widely are adequately prioritised.

This report is built on data analysis developed by LCP Health Analytics who kindly provided their services and support free of charge. To ensure the voices of the women affected and College members on the ground are central to the findings and recommendations in this report, the RCOG undertook surveys of both groups in 2021, followed by over 40 individual interviews to further inform our understanding of the issues.

A note on language and terminology

This report uses the terms ‘elective’ and ‘non-urgent’ to describe gynaecology waiting lists. This is because these terms are used interchangeably by the NHS, and are a simple way of describing those who are on a waiting list for diagnosis or treatment of a gynaecological condition that isn’t cancer. Cancer pathways in the NHS are not the focus of this piece of work.

The term ‘benign’ is often used alongside many of the gynaecological conditions discussed in this report. The RCOG has chosen deliberately not to use this term, and this decision is explained in detail later in the report.

Within this document, the terms woman and women’s health are used. However, it is important to acknowledge that it is not only women for whom it is necessary to access women’s health and reproductive services in order to maintain their gynaecological health and reproductive wellbeing. Gynaecological and obstetric services and delivery of care must therefore be appropriate, inclusive and sensitive to the needs of those individuals whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth.

As O&G is the only speciality which is almost solely used by women and those assigned female at birth, this report fully considers whether this plays any part in how gynaecology services have been prioritised in the delivery of NHS services.

Waiting lists in gynaecology have grown dramatically since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a combined figure of

on waiting lists across the UK as of December 2021iv - just over a 60% increase on pre-pandemic levels. This section of the report looks in detail at the length of gynaecology waiting lists in England with the support of the LCP Health Analytics Waiting Lists Tracker, including how these vary geographically. It also looks at the different data available across Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

It is very likely that the increase in COVID-19 cases caused by the arrival of the Omicron variant over the months following the publication of the data used in this report resulted in these numbers continuing to increase, possibly at a greater pace than previously. Cancellations will have been reported due both to the need for surge capacity for possible hospitalisations, as well as staffing shortages caused by staff isolating.

A note on data

Data collection and reporting of waiting lists differs across all four UK nations. This means it is not possible to make accurate comparisons between nations in many instances, and we advise against doing so. What the available data shows is a pattern of significant growth in the number of women on waiting lists for elective gynaecology, and that women are waiting considerably longer for care now than before the pandemic, wherever they are in the UK.

In terms of publication, data across all four nations is published at different intervals. In England and Wales, data on waiting lists is published monthly. In Scotland and Northern Ireland, data on waiting lists is published quarterly and the most recent data is from December 2021. To reflect this, where data is combined or looked at comparatively across countries, data for all nations is used up to December 2021.

To understand more about the methodology behind some of the data analysis in this section, LCP Health Analytics has provided a summary here.

As at December 2021 there were:

795 patients per 100,000 on the waiting list in England (56% increase since pre-pandemic)

802 patients per 100,000 on the waiting list in Scotland (94% increase since pre-pandemic)

1,330 patients per 100,000 on the waiting list in Wales (62% increase since pre-pandemic)

1,947 patients per 100,000 on the waiting list in Northern Ireland (42% increase since pre-pandemic)

All four nations’ gynaecological waiting lists increased substantially over the course of the pandemic. Although Scotland shows the greatest percentage increase, it is important to note that this increase is proportionate to the pre-pandemic waiting list in Scotland, which was lower relative to population than other UK nations.

Data shows us that by January 2022, there were 457,000 patients on the waiting list for gynaecology in England, compared to just over 286,000 in February 2020. This is an increase of 60% since the start of the pandemic, the highest percentage increase of any specialty, and one of the three highest specialties in terms of volume increase. This is against a backdrop of gynaecology already increasing faster than other specialties, with analysis showing it has increased by 90% since April 2018.

The NHS Constitution in England establishes that patients should be able to start consultant-led treatment for non-urgent conditions within a maximum of 18 weeks following referral from a GP. In England, the NHS target is for 92% of patients to have a referral-to-treatment (RTT) time of less than this maximum of 18 weeks. This is measured from the day a referral is received by the hospital or gynaecology department, and ends when treatment begins. In gynaecology, this could mean an admission to hospital for an operation or treatment, starting a treatment pathway outside of hospital, having a medical device fitted, or agreeing with the gynaecology team to ‘watch and wait’ ahead of possible further treatment or care.

The number of women waiting over 18 weeks from referral to treatment had already reached nearly 47,000 before the start of the pandemic in February 2020. That equated to 84% of women being treated within 18 weeks. It is now the case (as of January 2022) that over 180,000 women are waiting over 18 weeks from referral to treatment in gynaecology – a 383% increase. The percentage of women and people waiting over 18 weeks reached 40% in January, higher than the average for all specialties (36%).

Analysis shows that gynaecology has seen the largest percentage increase of those waiting more than 18 weeks from referral to treatment, both from April 2018 to January 2022 (575%) and from just before the pandemic began in February 2020 to January 2022 (286%) – equating to nearly 134,000 more women waiting more than 18 weeks now than when the pandemic began.

NHS England also measures the numbers waiting more than 52 weeks for treatment, as part of a ‘zero tolerance’ policy on patients waiting over a year for care. In February 2020, there were just 66 women on the gynaecology waiting list for over 52 weeks (a cohort often described as ‘long waiters’). At its peak in March 2021, this figure reached over 26,200 and still stood at 24,800 women at the end of January 2022. This means that the number of women waiting over a year for treatment has gone from less than one in 1,000 women on the waiting list before the pandemic to more than one in 20. Later in this report we look at what a wait this long means for the women behind the statistic.

The most recent data available shows that by December 2021 there were over 42,100 women and people on the waiting list for gynaecology in Wales, compared to just over 26,000 in February 2020. This is an increase of 62% since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The RTT pathway in Wales has an ambition of 95% patients waiting less than 26 weeks from referral to treatment, and no patients waiting more than 36 weeks for treatmentvi.

The number of women waiting more than 26 weeks from referral to treatment for gynaecology in Wales had already reached over 4,000 before the start of the pandemic in February 2020, and has now reached more than 21,500 as of December 2021 – a 438% increase. Against the target set by the NHS in Wales to see 95% of patients in less than 26 weeks, of the patients currently waiting to be seen, over 50% are waiting more than 26 weeks.

The NHS in Wales also measures the number of patients waiting over 36 weeks for treatment, this is the point at which people are considered ‘long waiters’. In February 2020, 823 women on the waiting list for gynaecology had waited over 36 weeks from referral-to-treatment. By December 2021, this figure had reached 16,624 – meaning nearly two in five women (39%) on the waiting list were waiting over the national target of 36 weeks to start treatment.

The most recent data available shows that by December 2021, there were over 43,800 women on the waiting list for gynaecology in Scotland, a 95% increase since the start of the pandemic.

In Scotland the referral to treatment (RTT) pathway for elective care is 18 weeks. The Scottish Government target states that 90% of patients should move from referral through to treatment in less than the 18 week target. Under this 18 week standard, health boards should ensure that patients are seen for an outpatient appointment within 12 weeks of referral, and having received a diagnosis and agreed treatment, that patients receive inpatient or day case treatment within 12 weeksvii.

Before the pandemic, the percentage of women and people waiting over 12 weeks for their initial outpatient appointment was only 13%, and this has now risen to 54%. For those waiting for inpatient or day surgery, the percentage of women waiting over 12 weeks has risen from 26% pre-pandemic to 68% as of December 2021.

The most recent data available shows that by December 2021, there were more than 36,900 women on the waiting list for gynaecology in Northern Ireland, a 42% increase since the start of the pandemic.

In Northern Ireland, targets for waiting times are more markedly different to the other UK nations, as the entire patient journey from referral to treatment is not collated or reported. Instead, the waiting times targets look at different parts of the pathway individually, measuring patients waiting for outpatient appointments, diagnostics and inpatient care all separately. It has been recognised in a Northern Ireland Assembly research paper that it is not possible to accurately estimate the length of time a patient is in the system from referral to treatment, because not all elements on the pathway are recordedviii. However, before the pandemic estimates indicated possible referral to treatment times of over four years in some cases.

Outpatient waiters are defined as the number of patients waiting for their first appointment in secondary care from a referral. The target for outpatients is that 50% of patients should wait no longer than 9 weeks for an initial outpatient appointment, with no patients waiting over 52 week. At the start of the pandemic (as of March 2020) waiting lists were already long, with 25% of women on the list waiting over 52 weeks for an outpatient appointment, which has now risen to 38%.

The waiting list for inpatient or day case treatment is made up of patients waiting either for admission to hospital overnight or for treatment within a day, and the target for this waiting list is that by March 2022, 55% of patients should wait no longer than 13 weeks for treatment, and again that no patient should wait longer than 52 weeks. At the start of the pandemic (as of March 2020) waiting lists for inpatient surgery already showed 30% of women waiting over a year for surgery, this has risen to 58%.

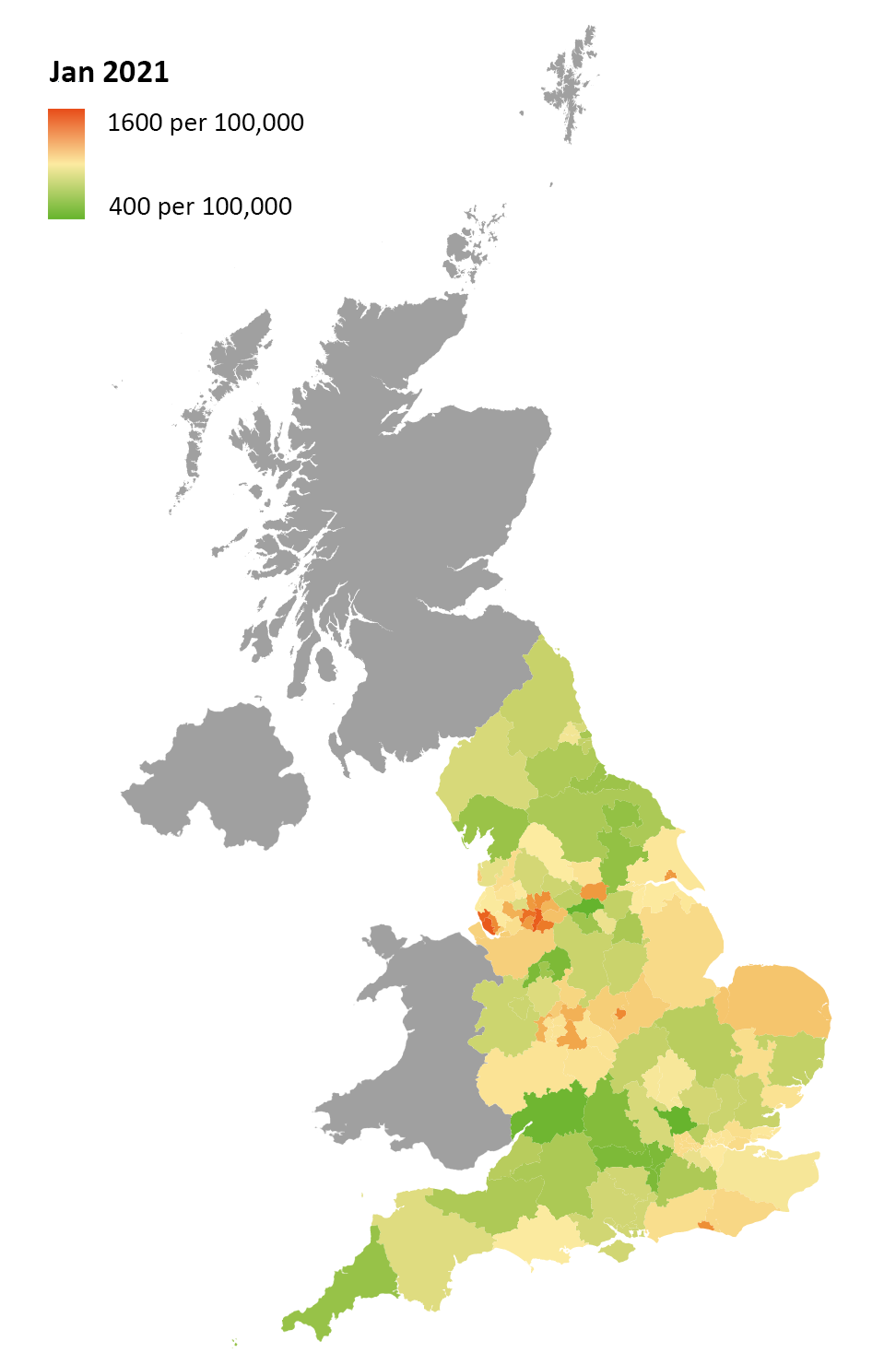

One of the major points of concern in relation to the growth of NHS waiting lists is the difference in waiting times depending on geographic location. The NAO report on NHS backlogs and waiting times in England highlights that ‘patients in some parts of England are much more likely to experience long waits for elective treatment than patients elsewhere’ and shows that patients in the worst performing sub-regions were more than twice as likely as patients in the best-performing sub-region to have been waiting over 18 weeksix. From discussions with members in devolved nations, there is a feeling this geographic variation is replicated across the UK.

Analysis of gynaecology waiting lists in England reflects this overall pattern in waiting list numbers, showing significant geographic variation both in absolute numbers, and proportionate to population size. Looking at breakdowns by region, the patterns of difference between regions that existed before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic have generally continued throughout.

The North West, which as a region had the longest waiting lists per 100,000 prior to the pandemic, was still in this position as of November 2021. On the other hand, the South West and the North East and Yorkshire, which had the shortest waiting lists per 100,000 prior to the pandemic, have both kept this position as of November 2021.

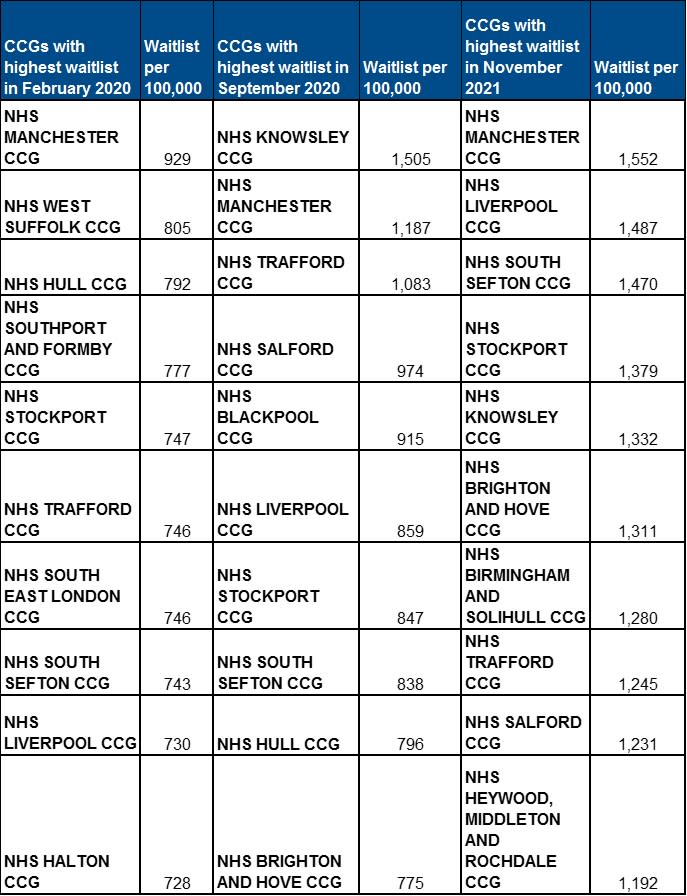

Looking at individual Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) the geographic variation shown at a regional level is generally replicated, with some outliers. Analysis up to November 2021 shows that eight out of 10 CCGs with the highest waiting lists by population were in the North West, an increase from seven out of 10 CCGs in February 2020.

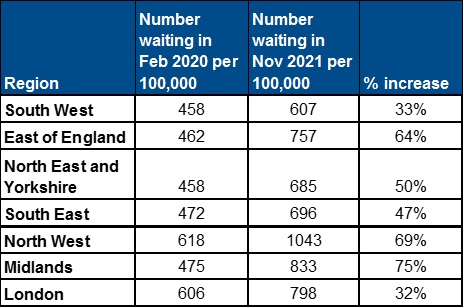

Table 1: CCGs with longest waiting list February 2020, September 2020 and November 2021

This report considers whether the pandemic had continued the patterns of difference between different regions or exacerbated them. To do this, we considered the increase in waiting list by population size in each region between February 2020 and November 2021. It showed a slightly different picture, with waiting lists growing the least sharply in London and the south, growing more sharply in the East of England and the north, and most sharply in the Midlands. This is exemplified best by the difference between waiting lists in the North East and Yorkshire and the South West through the pandemic, regions with the lowest waiting lists per population size before the pandemic (both with 458 people per 100,000 in February 2020). Growth during the pandemic in the North East and Yorkshire has been marginally larger proportinate to the population (50%) compared to growth in the South West region (33%). This could be for a variety of reasons, including the lesser impact of COVID-19 on hospitals in the South West region compared to the North East and Yorkshire. By region, there is not much variation between the areas with the longest waiting lists by population, and those with the longest waiting lists in absolute numbers. RCOG members suggested that regions that have experienced smaller increases in waiting lists might have also benefitted from more mutual aid from neighbouring providers who were less impacted by COVID-19.

Figure 1: Number of patients on the waiting list per 100,000 in February 2020, March 2021 and November 2021 by region

Table 2b: Number waiting in February 2020 and Number waiting in November 2021 per 100,000 and percentage increase by region in England

The disparity between waiting lists by area is stark. As of November 2021, the CCG with the highest waiting list per 100,000 had a waiting list over five times larger than that of the CCG with the lowest waiting list per 100,000. The CCG with the lowest number of long waiters only had two women per 100,000 waiting over 52 weeks for care, whereas the CCG with the highest number of long waiters had 289 women per 100,000 waiting this long. This creates a huge postcode lottery in the length of time women and people wait for care and treatment in gynaecology.

Although disparities in waiting list size are significant across all specialties, they are particularly pronounced in gynaecology, with the percentage difference between the CCGs with the smallest and largest waiting list per 100,000 in gynaecology (513%) considerably higher than the percentage difference between the corresponding CCGs when you look at all specialties combined. The percentage difference is also much less pronounced in other specialties with long waiting lists, such as orthopaedics (287%) and ophthalmology (377%).This analysis relates to data up to November 2021

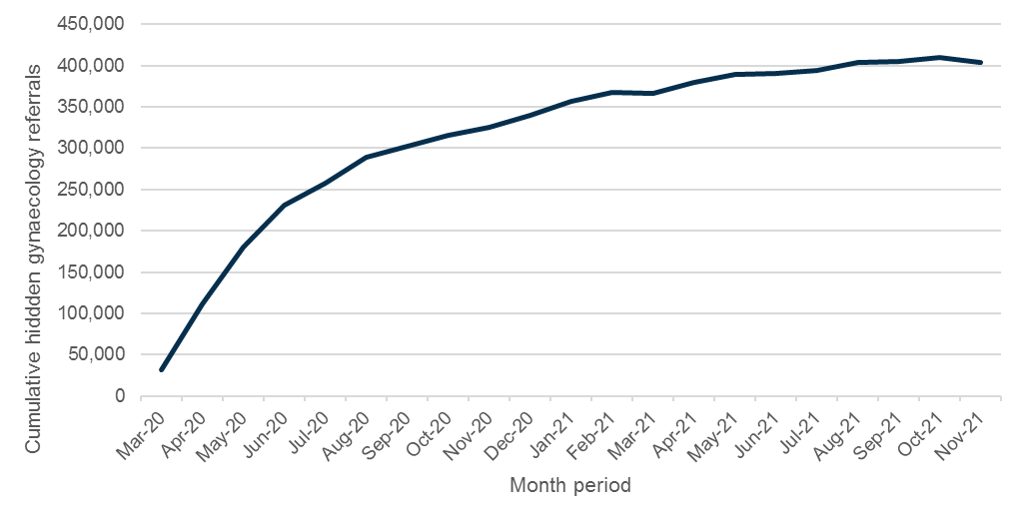

Analysis produced by LCP Health Analytics on behalf of the RCOG indicates that there appear to be approximately 404,000 women who would have been expected to join the waiting lists for gynaecology in England in the 20 months since the start of the pandemic up to November 2021, who have not. This suggests an estimated total unmet need of nearly twice what is shown in the current known waiting list, reaching over 840,000 women.

Figure 2: Cummulative hidden referrals March 2020 - Nov 2021

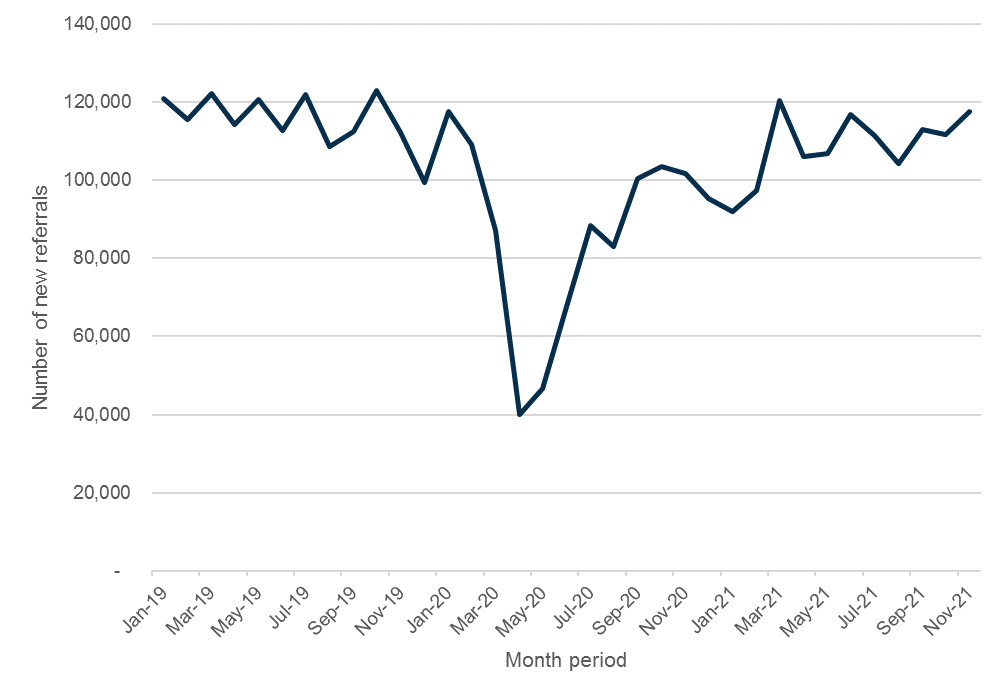

Rates of these missing referrals increased rapidly at the start of the pandemic, with 60% occurring in the first four months from March 2020. In recent months, the rate of increase of missing referrals has slowed. Gynaecological monthly referral rates were generally lower each month of the pandemic than pre-pandemic with the waiting list size increasing due to fewer people leaving the waiting list and an increasing hidden need. The exceptions were March and November 2021 when monthly referral rates were higher than pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 3: New gynaecology referrals to treatment by month since 2019

Hidden need is best understood by looking at referrals that are missing from the system compared to pre-pandemic years. It has been a common topic of discussion in relation to NHS elective recovery and waiting lists. The NAO explains the lower levels of referrals seen during the pandemic as both some people avoiding healthcare settings because of fear of the virus or to reduce demand on the NHS, and others possibly having difficulty getting appointments with their GPs, consultants or diagnostic services.x

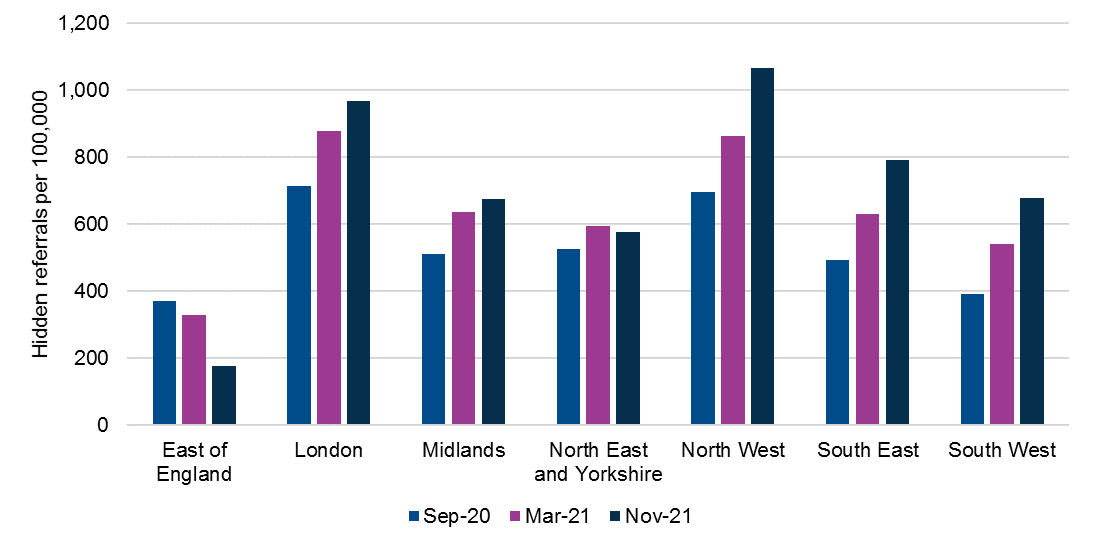

Figure 4: Total hidden need by region per 100,000

As of November 2021, London had the highest total number of hidden referrals (nearly 86,900) which may explain in part why its waiting lists have increased less both per population and in absolute volume compared to other regions. The North West had the second highest number of total hidden referrals (over 75,300) and the highest number of hidden referrals when adjusted for population size (over 1,000 per 100,000). This adds to the concern about huge disparities between existing waiting lists, in particular in the North West, where the majority of the CCGs with the highest hidden referrals are located.

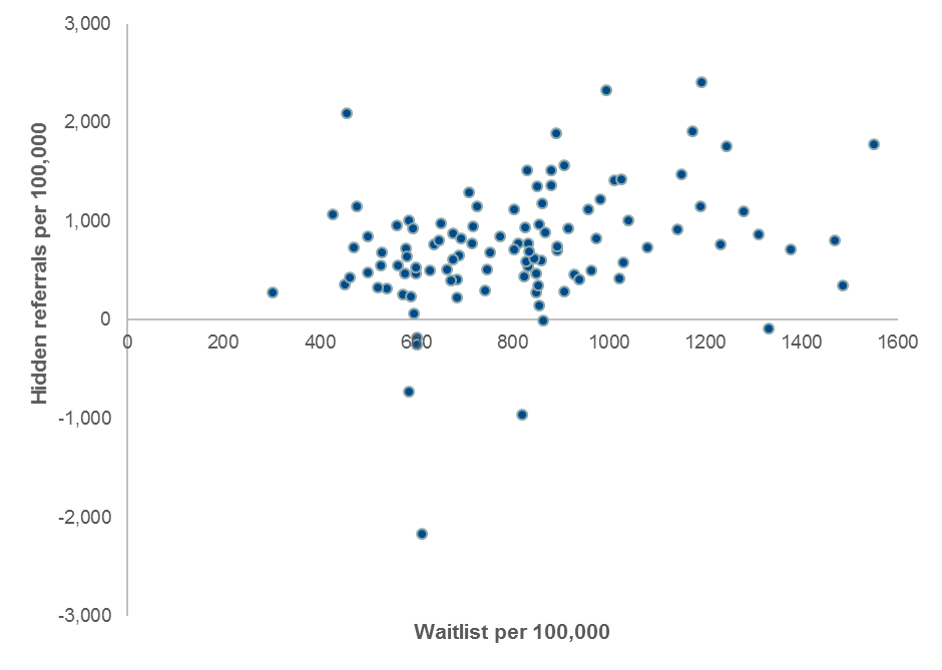

Comparing the number of hidden referrals by population size to the current waiting list by population size shows that the number of hidden referrals tends to be higher in CCGs with higher waiting lists per population.

Figure 7: Total hidden gynaecology referrals in England as at Nov 2021 by CCG and total waiting list per 100,000 people

To make sure the right action is taken to reduce the backlog in gynaecology and more widely across elective care, it is important to have a detailed picture of waiting lists. This means understanding where in the system women and people are waiting: are they waiting for an initial outpatient appointment, general tests or scans to confirm a diagnosis, a diagnostic procedure within the gynaecology unit, or for a procedure, either outpatient, inpatient, or as day surgery?

Survey responses and interviews with RCOG members identified that there is variation in where women are waiting. In some areas outpatient lists are growing and there are concerns about significant numbers of patients not being seen at all for an initial appointment. In other areas, initial appointment waiting times have reduced to pre-pandemic rates (either through additional clinics, telephone or remote clinics) but waiting lists for surgery are growing longer because of difficulties accessing surgical capacity.

Understanding waiting lists is not just important at a local level, but also for the NHS at a national level. It allows for more effective investment by focusing capacity where it is most needed. In Scotland and Northern Ireland, national waiting lists figures are broken down to show numbers of patients waiting for inpatient/day surgery, and those waiting for outpatient appointments. The RCOG encourages the NHS across all four nations to consider publishing breakdowns of current waiting lists in a similar manner both locally, regionally and nationally.

Understanding local and regional disparities in gynaecology backlogs also allows the NHS to identify any opportunities for mutual aid between different areas where capacity constraints differ. For example, if there are units where outpatient capacity is limited but surgical capacity is higher, there might be an opportunity to work collaboratively with other areas experiencing the opposite challenge. We encourage the NHS to consider how it could reduce disparities in waiting list numbers by working across larger footprints, including exploring whether women might be willing to travel further to access care sooner. In Wales, there is potential to improve regional collaboration through the Welsh Health Specialised Services Committee (WHSSC) allocating funds to key specialist services access in gynaecology.

Even prior to the pandemic, the Public Accounts Committee concluded in a report on NHS waiting times that ‘national health bodies lack curiosity about the impact for patients of longer waits and how often this leads to patient harm'x. The Committee recognised that understanding the impact of longer waits is an important way of managing the risks inherent with a backlog in care, something that has never been more important given the current length of waiting lists across the UK.

Using data to understand the length and nature of gynaecology waiting lists is essential to taking the right action to reduce the backlog in elective care across the NHS. Understanding the impact of waiting longer for care on individual conditions and specialties is also crucial to ensuring that the NHS recovers in a fair and equitable way.

Central to this report is telling the stories of women on gynaecology waiting lists, stories which are too often not heard. This section of the report features experiences of individuals who are currently or have very recently been on a waiting list. Alongside their experiences, we explore the results of our survey of women on waiting lists for gynaecology, which received over 830 responses.

This section also explores the concerns of RCOG members working in gynaecology across the UK. It highlights the key findings from our members’ survey, which received 135 responses, and learning from over 25 interviews with consultants and trainees working in gynaecology.

Given the dramatic growth of gynaecology waiting lists in recent years, it is no surprise that 92% of women who responded to our survey told us that the pandemic made it more difficult to access the care they needed, and over 90% told us that part of their diagnosis or care was delayed or cancelled due to the pandemic. Of the women who responded to our survey:

Challenges accessing the right care and support for many gynaecological conditions is not a new experience for women and has been a result of the lack of investment and attention given to women’s healthcare historicallyxi. As one RCOG member said ‘women’s health is always at the bottom of the pile’. This is the thread that draws together the available data and the experiences of both women and RCOG members.

RCOG members working in gynaecology are clearly concerned that this lack of attention will continue to be replicated as the NHS recovers. The majority of members we surveyed indicated very low levels of confidence that gynaecology was being adequately prioritised in the NHS recovery planxii.

We recognise that challenges accessing the right care and support in gynaecology are not just a symptom of longer waiting lists. There are many reasons that women and people face barriers accessing care including a lack of high-quality information on many gynaecological conditionsxiii, a lack of education and knowledge in primary care leading to inadequate supportxiv, and a lack of investment in research focused on women’s healthxv. However, both women and RCOG members have been clear that the growing length of waiting lists in gynaecology, which had begun before the pandemic, is becoming an even bigger obstacle to accessing care.

The women who took part in our survey felt strongly that communication whilst they were on a waiting list was inadequate. When asked how they would rate the communication from their local healthcare provider, 39% of women responding chose the rating ‘very poor’ and another 31% chose ‘poor’, with less than 10% of respondents opting for positive ratings.

Many women recognised that they were likely to have a long wait before receiving care, but felt that having a clearer idea of the likely wait would make it easier for them while they remained on a list. They highlighted being able to plan ahead without the constant worry over missing an appointment or procedure, and being able to better mentally manage living with symptoms with an ‘end date’ in mind, as potential benefits of being given an indicative waiting time.

In its report following the first wave of the pandemic, National Voices outlined good practice principles for designing a more positive experience of waiting, and highlighted the importance of using easily understood language, checking in during waits, and explaining to patients how decisions are made about waitsxvi. The results of our survey suggest these things are not consistently being done. The results also suggest that guidance on good communication with patients waiting for care co-produced by the NHS in Englandxvii is not being put to use by providers.

Alongside work to reduce the length of time women and people are spending on gynaecology waiting lists, immediate action must be taken to improve their experiences whilst waiting. There needs to be much more substantive information, support and communication for those who are waiting longer. This should include national action to outline and signpost to existing best practice for providers as part of the recovery plan, which has the potential to have a marked impact on the experience of those waiting. The RCOG is keen to work alongside the NHS nationally and locally to understand what good support and communication looks like specifically for women on gynaecology waiting lists.

Having a comprehensive understanding of the impact of waiting longer for gynaecology care and treatment, and how this compares and relates to other areas of elective care, is essential in understanding how to prioritise care and treatment during the NHS recovery. Not enough is known about the impact of waiting longer on aspects of disease progression for many gynaecological conditions, including how this progression might impact the care and treatment women need.

The women and RCOG members surveyed and interviewed for this report made it very clear that there has been a significant impact on the progression of disease, and associated symptoms, of many common gynaecological and urogynaecological conditions as a result of longer waiting lists. More than 75% of women reported that their symptoms had worsened whilst on the list, and only 4% said that their symptoms had improved.

Just under three quarters of respondents to the RCOG member survey said they were seeing patients with more complex care and treatment needs as a result of waiting longer for care. Members shared their particular concerns which are explored in more detailed below.

Sameerah is in her 20s and lives in the South West with her husband. She is currently on the waiting list for surgery at a specialist endometriosis centre, where she has been told the waiting list is 18-24 months.

I first had a laparoscopy in 2018 where I was diagnosed with endometriosis. It was around two years later, that I started to experience increasing pain once again. A scan showed I had large endometriomas all over my ovaries and I was referred to a fertility doctor as I was also struggling to conceive. I was then referred to the endometriosis specialist centre by the fertility team and I was told I would need to have those cysts drained before I could start fertility treatment. The cysts were weighing down on my ovaries and causing distortion that prevented egg extraction.

When I had an appointment at the endometriosis specialists I had an ultrasound which caused a cyst to leak, and I was then in agony for months. My husband would come home from being out of the house and find me lying on the floor in pain just waiting for it to pass. We both felt so helpless. I look back at that period and I’m not sure how I got through it. Working from home was the only thing that made it just about manageable.

Shortly after, I found out that the waiting list for the surgery I needed was 18-24 months. As I was in so much pain, I paid privately for the removal of endometriosis, but following an investigative laparoscopy the consultant felt he didn’t have the skills to operate as it was so severe, so I’m back to square one.

The stress and anxiety of the waiting whilst I have been in pain and since we have been trying to conceive has been at some points unmanageable. I am exhausted mentally, emotionally and physically. Sometimes when the pain takes over I’m unable to leave my house to go to work, and see friends and family. It can make me feel so isolated and alone. Sometimes I don’t want to bother making plans in the first place, and then I end up completely shutting myself off. It’s just so tough constantly waiting.

Photo by Imani Bahati on Unsplash

There was consensus amongst the RCOG members we surveyed and interviewed that they were seeing increasing numbers of women and people with more advanced endometriosis as a result of waiting longer for both for initial appointments, and for treatment. Although the extent to which endometriosis is a progressive disease is not clear, there is evidence to show that when untreated the condition may progressxviii. The World Health Organisation notes that early diagnosis and management may slow or halt the natural progression of the disease and reduce the long-term burden of symptomsxix.

There was a strong feeling amongst members that the pelvic pain commonly associated with endometriosis was becoming more severe due to women waiting longer for care, and that pain management was becoming increasingly difficult for many women. Some members reported an increase in the number of women attending A&E or acute gynaecology services in extreme pain. Interviewees also pointed out the need to consider pain tolerance over longer periods of time, noting that pain scores for many women may not have increased dramatically, but the impact of living with the same level of pain for longer periods of time cannot be underestimated. One woman explained in her survey response ‘the implications of not knowing when or how I might start to feel better in myself and not have the constant worry that I’m going to be in excruciating pain every month has definitely started to take more of a toll.’

Although it is important to recognise that the progression of disease and the severity of symptoms experienced do not always correlate when considering how to prioritise waiting listsxx, it is also vital to consider how treatment options are likely to change with progression of disease, with more invasive and complex surgery becoming more necessary with advanced stages of endometriosis.

RCOG members we surveyed and interviewed reported further concerns that it is the women with more complex and advanced cases of endometriosis, where longer and more complicated inpatient surgery is required, who are waiting the longest for surgery. This is particularly the case where there is a requirement for a multi-disciplinary surgical team, often including a bowel or bladder surgeon. One interviewee told us that the highest proportion of those waiting over 52 weeks on their waiting list were waiting for complex endometriosis surgery. Risking the progression of disease for even a proportion of the women and people currently on waiting lists for suspected or diagnosed endometriosis is likely to require more capacity in the system in the long-run, as more complex inpatient surgery is needed for a greater number of women than would previously have been the case.

Lucy is in her 40s and lives in London. She has been referred to a specialist endometriosis clinic following an initial appointment with a gynaecologist, and is waiting for an appointment.

I was first diagnosed with endometriosis over twenty years ago, and since then I have been able to manage my condition and symptoms with medication. It is only in the last year where my endometriosis has flared up rapidly and the pain it is causing me has completely taken over my life.

In March of 2021 I experienced sudden extreme pain and went in to A&E, where they admitted me and spent a few days establishing for certain that it was my endometriosis causing it. At that point I was referred to gynaecology for an appointment. I assumed because of the pain I was in this referral would be quick, but I waited a few months for any contact, and then received an appointment 5 months in the future. I was so desperate at that point, I paid privately to see a gynaecologist who told me that I likely needed a hysterectomy. I’m still waiting on an appointment in the NHS to get me on a waiting list for the surgery I need.

When it is bad, the pain is so acute I am not able to leave my house. It leaves you stuck making the decision between extreme pain or painkillers that are so strong they stop you being able to do anything but lay on the sofa and wait for it to pass. I’ve been in to A&E with the pain five times whilst I have been waiting, even though I know there’s not really much they can do.

All aspects of my life are messed up by this pain. I have always worked until I had to take time off with breast cancer in the last few years, I had just started a brand new job and was ready to move forward with my life when the pain started last year, now I struggle to work and am having to claim benefits for the first time in my life. I want to meet a partner, but I know it’s just too complicated to manage at the moment. I constantly feel like I’m letting down friends and family because I can’t make plans and struggle to be social. Last year on my birthday, rather than getting to a music festival and going to dinner with friends, I was in such pain that all I did that day was go out for a drive and have a cup of tea with my mum, just so at least I’d left the house.

I’ve been told it could be two years until I have a hysterectomy. Am I supposed to carry on my life like this until then? I am stuck in limbo. I am so deeply angry and upset that this has happened to other women.

RCOG members raised concerns about the impact of heavy menstrual bleeding on many women. They reported that this has gone unmanaged considerably longer due to the length of waiting lists for gynaecology, but also due to many challenges accessing community and primary care services during the pandemic. Heavy menstrual bleeding is likely to fluctuate for many women throughout their life course, but is also caused by gynaecological conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), uterine fibroids and endometriosisxxi.

It is common for women and people with heavy menstrual bleeding to see their GP initially, and in many cases they can be supported effectively in primary care, often with hormonal and non-hormonal treatments, without the need for further investigationsxxii. For women with underlying disease causing their heavy menstrual bleeding, management in primary care can be less successful, and they will need to see a specialist for further investigations and possible treatment.

The RCOG members we surveyed and interviewed raised concerns that women experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding were having to wait too long to see a specialist and this was causing unusually high rates of anaemia, with women being admitted to hospital as emergency admissions requiring iron infusions or blood transfusions. One member explained their worry ‘if someone has heavy bleeding and you can’t manage them hormonally you don’t know what will happen next. You get all these anxieties about the length of time these women are having to wait’.

Many of the women who shared their experiences of heavy menstrual bleeding told us it was having a huge impact on them physically, with many saying they were experiencing heavier and more frequent bleeding while they were waiting. This was particularly the case for women where uterine fibroids had been identified as the cause, with regular flooding and clots a feature in many women’s experiences. Some women reflected the concerns of our members, explaining that they had needed blood transfusions because they had been waiting so long for treatment.

For women with uterine fibroids, heavy menstrual bleeding, including flooding and passing of clots, is a common symptomxxiii. As fibroids increase in size, their impact becomes more significant, including the likelihood of worsening heavy menstrual bleeding and pain. Fibroids do not always grow but when they do, women have to manage more severe symptoms the longer they wait. In addition, the treatment options available to them change if fibroids growxxiv, which may result in more invasive and time-consuming medical, hormonal and surgical interventions for a larger proportion of women and people with this condition.

Ovarian cysts very often disappear without the need for treatment, but for a small number of women the size or location of their cyst means it causes symptoms including pain, bloating and heavy or irregular periods. Ovarian cysts can also rupture or twist and cause similar acute symptoms. When women are experiencing these symptoms they are usually referred to a gynaecologist, and the cysts are sometimes removed through surgery.

The RCOG members involved in this report said they were seeing a number of women with larger ovarian cysts that had grown whilst they were on a waiting list, with worsening symptoms as a result. Some also reported that they were seeing more women with ovarian cysts in emergency settings with acute torsion or ruptured cysts. Ovarian torsion, if not identified and treated quickly, can result in loss of the ovary. The surgery to remove ovarian cysts is minimal access wherever possible, making recovery quicker, but where cysts have become too large open surgery can be needed, making recovery times longer. There is also a risk the whole ovary may be lost having an impact on long term reproductive health and fertility.

Michelle lives in the South East. She has been seeing her GP on and off for 16 years for issues with her periods, and very recently had surgery to remove two ovarian cysts and diagnose stage 3 endometriosis, following over a year on a waiting list for surgery.

Around the start of 2020, I started to develop abdominal pain which was getting increasingly worse as time went on. I waited as long as I possibly could to see the GP as I was worried at the start of the pandemic about bothering the NHS, but eventually my pain was so acute I decided I needed to book an appointment in the July. In August 2020, my GP was able to diagnose me with two cysts on my ovary which were caused by endometriosis, and I was then referred in to gynaecology for surgery to remove the cysts.

Whilst waiting for surgery the pain continued to worsen. I found it a huge adjustment going from someone who was quite fit and healthy, to living with daily chronic pain. I had severe pain localised to my right ovary, I couldn’t do any exercise and I struggled to take part in many social events. I’m self-employed and was able to take far less work to avoid the pain getting out of control. I’m an actor and it stopped me taking jobs because the physicality of the roles, or even the costumes for many of them, were too difficult to manage with the pain I was experiencing.

I had the surgery in December of 2021 and I can’t describe the relief I feel. My abdominal pain, which was being caused by the ovarian cysts, has seemingly gone, so I’m now only needing to take pain killers on my periods instead of every day, and I’m just so grateful it has finally been done. I still do live with uncertainty as I didn’t have a conversation with my consultant before being discharged, and I was originally told I may need more than one surgery, so I’m waiting for my outpatient appointment which is scheduled for six months’ time, and really hoping that isn’t cancelled or delayed.

One thing that didn’t hit me until a few days before my surgery was the issue of fertility, when my surgeon rang me to discuss the fact that my recent blood test results had showed my ovarian reserve was low, and that had made her uncertain about whether or not she should operate. I know that when I’d had those tests the year before, just after my diagnosis, I was told they were about right for my age. It was then that I realised that being on a waiting list was affecting my fertility, and that’s not something you can just get back, that was a permanent impact.

Zoe is in her 30s and lives in the South West. She is waiting to see a gynaecologist following a referral from an emergency clinic appointment.

I’ve had trouble with my periods since they started, and I was diagnosed with endometriosis following an exploratory laparoscopy in May 2018, during this surgery they drained a cyst on my right ovary. After increasing pain and symptoms, following a long wait, I had extensive surgery for my endometriosis in September 2020.

Recovery was good, and I felt as if the pain had improved massively almost as soon as I woke from my surgery. But very soon it started worsening again, month after month. In July of 2021 I suddenly got this sharp pain through my left side that wouldn’t let up, it made me sick, gave me the sweats and made me feel very faint. I was referred to an emergency gynaecology clinic at a different hospital, where they identified an endometriosis cyst on my left ovary and referred me back to my local hospital for an emergency appointment. They were also worried I had an abscess in my fallopian tube as it was full of fluid.

Over six months on and I am still waiting for my emergency appointment. My pain is worsening and I’m really struggling to keep going, I regularly push myself to the extreme at work so I am able to sleep through some of the pain at night. My work is very physical, and I never want to not be able to throw myself in to it, but there are some days where I just can’t do everything I need to. I’m often sick before I go into work to manage the pain, which feels unsustainable.

Even a rough idea of when I’ll next be seen, and what treatment I might need, would help me to manage in the meantime.

The progression of urogynaecological conditions whilst women have been on waiting lists was one of the most common concerns for RCOG members, with many describing seeing higher numbers of women and people with worsening pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence. The waiting lists for gynaecology are one of the key causes for this progression, alongside barriers to accessing primary and community care during the pandemic, where conservative treatments (such as fitting of pessaries and pelvic floor physiotherapy) would have prevented progression in many instances.

The RCOG members taking part in our survey and interviews flagged concerns that long waits for treatment in urogynaecology were causing complications including procidentia (a severe form of pelvic organ prolapse), bleeding, infection and ulceration, as well as more women presenting with ureteric obstruction and urine sepsis. One member told us they had seen an increase in irreversible kidney failure as a result of women waiting so much longer for care. These complications have a significant impact on the women affected, who have to manage their worsening symptoms. These women also often then require more invasive and complicated surgery and face living with more complex long-term health needs, adding to the required capacity in the system.

There is also concern about the women across the UK who are waiting for mesh removal surgery. The pandemic has, to a certain extent, hampered the ability of new mesh removal centres to reduce the waiting lists of women waiting for surgery, and RCOG members highlighted the importance of ensuring these services were fully restored as soon as possible. Members highlighted that mesh removal for complications that involve mesh perforated into an organ (such as the bladder, urethra or bowel) should take place within six weeks, and ‘this is definitely not happening’.

The impact on women affected by mesh cannot be underestimated. It is vital that services for mesh removal have sufficient capacity and support to reduce waiting lists and ensure women are seen in a timely manner, with a recognition that women have been living with complications caused by mesh for many years.

RCOG members working in urogynaecology felt strongly that it was the worst hit of all areas of elective gynaecology, with one member saying:

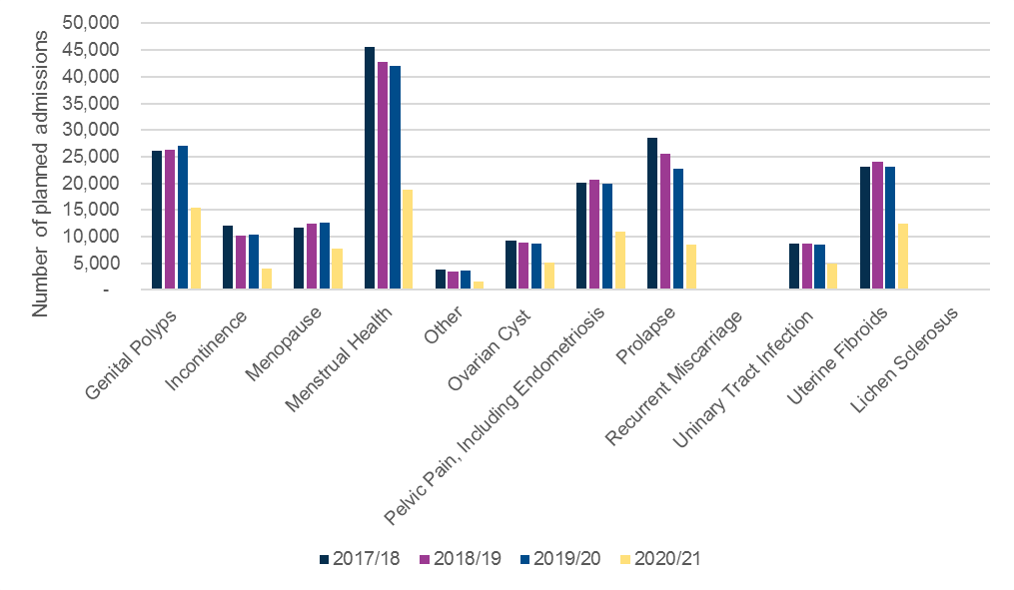

This is shown in the data available for condition specific codes in gynaecology between 2019/20 and 2020/21, with planned admissions for prolapse falling by 62% and planned admissions for incontinence by 61% (these are compared to falls of c.55% or less in other gynaecological conditions). Planned admissions for prolapse and incontinence surgery also fell between 2017/18 and 2019/20 by 20% and 15% respectively, indicating the lack of prioritisation for urogynaecology far before the impact of the pandemic.

This impact on urogynaecology was also reflected in training opportunities, with the RCOG’s 2022 workforce report highlighting that urogynaecology was the most heavily impacted area of sub-speciality training. The workforce report also shows that urogynaecology has the lowest number of sub-specialists, and has seen a fall in the number of trainees completing sub-specialty training in recent years. With an ageing population, this does not correspond with the likely future workforce needs in O&G.

Figure 8: Analysis of Hospital Episodes Data, published annually by condition code illustrate the difference in the number of planned admissions for individual conditions within gynaecology. The latest data available covers admissions up to March 2021.

The average age of women who need to access care in urogynaecology is generally higher than that of the rest of elective gynaecology. This is likely to have had an impact on decisions to treat women and people during the pandemic, where the risk of severe illness from contracting COVID-19 while in hospital was higher. Surgery in urogynaecology also more commonly requires inpatient stays, and the lack of access to inpatient surgery lists reported by our members might also have disproportionately affected the service.

However, across all of gynaecology there is a history of stigma and taboo, accompanied by a normalisation of symptoms that make women feel that what they are experiencing is acceptable, and they should continue to manage without help or intervention. No more so is this the case than in urogynaecology. There is a strong feeling among both RCOG members and the women we have spoken to that urogynaecology has been heavily de-prioritised before, during and after the pandemic. It is vital that the needs of these women are better met as part of NHS recovery.

Annie is in her 70s and lives in the South West with her partner. She is currently waiting for an initial outpatient appointment following a diagnosis of prolapse.

I was referred to see a gynaecologist in May 2021 and I’m currently waiting for an appointment, I have no idea how long I’ll have to wait but from the information on the hospital’s website it looks like it could be well over a year longer before I see someone. I am really wanting to avoid surgery if at all possible, and am hoping I will be able to get a pessary fitted, but I know the longer I wait, the less likely this becomes. I’m doing my exercises religiously, and I’m taking on all the advice I possibly can about the right things to eat and drink in the meantime, in the hope this will help.Various software programs are used to color the drawings and simulate camera movement and effects.

Whilst I wait I can feel my prolapse getting worse, and the symptoms that go with it. I’m getting more and more UTIs and I’m needing to go to the toilet a lot. I also really struggle with my bowels, and managing that is becoming increasingly difficult. It’s really having an impact on my mental health, I’m usually pretty strong and I’m an optimistic person, but I find it hard to find the strength to be positive about this, because I don’t see how it is going to improve.

What I find so frustrating is how simple I know trying a pessary would be compared to surgery, and how much less time and money it would cost. That on top of the fact that I want the choice to try it at least, I don’t want invasive surgery.

Rachael is 44 and lives in the North West with her husband and two children. She is waiting for treatment for her prolapse following an initial appointment with a gynaecologist, and is also experiencing difficult symptoms from the perimenopause.

It was in 2019 that I first saw a gynaecologist for prolapse and was referred both to a pessary clinic and to a women’s health physio. Since then, I have had multiple pessaries that haven’t managed to alleviate the symptoms from the prolapse, and I was put on the waiting list for surgery before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. I have been waiting ever since.

I have mixed messages each time I speak to a consultant or a member of staff at the hospital about when my surgery might be. I was initially told 18 months, and I was recently told it might possibly be another two years. In the meantime I am continuing to try different pessaries and working with my physio to manage whilst I wait.

I had to give up work last year because I just feel exhausted a lot of the time. I’m no longer interested in socialising unless I know I can sit down, or won’t be walking too far. I can’t even do gentle exercise without the pain that follows, it just aggravates it. I’m just trying to bring up two young kids, and keep physically well, and it makes everything so much harder. I feel like my whole life is on pause.

Sharon is in her 50s and lives in Scotland. In 2012, after experiencing stress urinary incontinence, Sharon underwent mesh surgery. Following her mesh surgery, she has experienced complications and now requires mesh removal surgery.

A couple of years ago, after years of pain, I decided to have a scan done privately to understand whether the mesh that I had inside me was the cause. The report showed that the mesh had split and was eroding, and I was recommended mesh removal and referred to a mesh removal expert in June 2019.

The mesh removal expert first needed me to undergo a cystoscopy to understand what was happening with the mesh. I had this cystoscopy in January 2020, and waited for a follow up which never happened. I phoned several times and was eventually given an appointment in June 2020, but soon after this was cancelled due to the pandemic. Throughout the rest of 2020 and the lockdowns that came with it, I waited with my symptoms worsening, and eventually I was given an appointment for July 2021.

When I finally saw the consultant in July, I was incredibly frustrated to find out that the cystoscopy I had in January the year before was no longer valid as it had been undertaken over 12 months ago, and therefore I needed another one. I am still waiting for the appointment for this next cystoscopy, and I know that once that scan takes place I will have to wait again for a long time on a waiting list for mesh removal surgery itself.

The cystoscopy in January 2020 showed that I had mesh in my bladder, and that it had cut holes in my urethra. My pain and my symptoms have worsened over the last two years. My pelvic pain is so bad I can barely walk, and I have to use a wheelchair to leave the house. I have urinary and faecal incontinence, and if I do leave the house I always have to take spare clothing with me just in case. There’s never a good day with my pain, it’s just the difference between moderate and severe. I constantly have to cancel plans and it has really impacted my mental health. It’s made me such an angry person, and I really never used to be angry.

I want to be able to work but I can’t, I am instead living off benefits and I feel like a cost. A cost to the NHS in all my many prescriptions, a cost to the Government in welfare benefits. I’m so desperate to be treated so that I can be in a position where I can go out and start making contributions to society again. At the moment, I just feel like I’m suffering and no one cares.

The majority of care and treatment for perimenopausal symptoms takes place in primary care. Women with amore medically complex background, or a diagnosis of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) can be referred to a menopause specialist in secondary carexxv.

As a result of growing waiting lists for outpatient care, many women experiencing extremely challenging menopause symptoms are not being seen and supported by a specialist in a timeframe that meets their needs. One RCOG member who specialises in menopause explained ‘these women are simply not being managed at all’.

Many RCOG members reported a move to remote appointments for menopause services as part of the pandemic, and most were positive about the flexibility this provided women. The British Menopause Society (BMS) has highlighted that the nature of menopause consultations lends itself well to virtual consultations, as a significant majority are conducted without the need for a physical examination. However, access to face to face consultations must remain available where neededxxvi.

The impact of challenging symptoms related to the menopause can have a detrimental impact on women’s quality of life, wellbeing, personal relationships and workxxvii. Ensuring that women can access specialist menopause care without long waits for outpatient appointments must be included in elective recovery planning.

Angela is in her 60s and lives in the North West. She has been referred to see a gynaecologist about her menopausal symptoms, and is waiting for an initial outpatient appointment.

About five years ago I started to recognise the symptoms that I was experiencing were likely caused by hormone changes in the menopause, and I was prescribed HRT and then had a coil inserted to manage irregular bleeding, and this seemed to manage my symptoms relatively well for a while.

In March 2021, I once again started experiencing worsening symptoms, my night sweats and hot flushes returned, and I also started to get new symptoms like joint pain in my hips and knees. I then started having real issues with intercourse and was experiencing pain in my vulva and my vagina. My GP prescribed me oestrogen cream to start with, which did help, but I was still experiencing pain, especially during sex, and I totally lost my libido. I was referred back to the gynaecology department.

Whilst I wait my anxiety has just got consistently worse, which has really dampened my self-confidence. I am experiencing pain and burning caused by vaginal atrophy, and I’m now starting to have urgency when I need to go to the toilet. Sex is no longer something I can contemplate because of the pain. Sex is so important for bonding in a relationship, and I find it difficult that it’s not there. I want to be able to share that with my husband, but it just hurts too much.

Karen is in her 50s and lives in the West Midlands. She was diagnosed with stage 1 uterine cancer four weeks before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and had a full hysterectomy with removal of uterus, tubes and ovaries three weeks later. She is waiting to see a menopause specialist within the gynaecology service, with an appointment currently scheduled in November 2022.

Having had a full hysterectomy weeks before lockdown, I had a phone call the following week to let me know that the surgery had gone well, but that they were delaying follow-up and discharging me because of the pandemic. I recovered quickly from the surgery, and at first felt everything had gone well.

It was only when I started experiencing lots of unexpected symptoms that I started to worry. First I had joint pain, and this was followed by a whole host of other issues including anxiety and depression, brain fog and breathlessness. After research on the internet, I realised that it was likely these symptoms were caused by my hysterectomy.

My symptoms continued to worsen over the summer of 2020 and I eventually contacted my GP. The practice nurse who has supported me a lot explained that they needed the advice of a specialist in gynaecology before they decided on treatment options for me, because I’d had cancer. I’m now stuck waiting for an appointment with a specialist so that I can access treatment and hopefully much better manage the symptoms I’m experiencing. Whilst I wait, I’m still struggling unnecessarily.

The potential impact on fertility

The potential impact on fertility of leaving some gynaecological conditions untreated for longer is significant, and a concern raised both by the RCOG members and women we surveyed and interviewed. Some of those women and people are in the process of fertility treatment, others are considering how waiting for care now might affect their plans for a family later in life. There is clear evidence that some gynaecological conditions impact fertility, including endometriosisxxviii and fibroidsxxix, plus fertility decreases with age, so many women waiting for treatment prior to trying to conceive will have less chance of getting pregnant because of their long wait for treatment.

Women told us how their fertility treatment had been put on hold until they were able to get surgery for a gynaecological condition, either because the condition may make IVF treatment less possible (for example if cysts or fibroids may make egg extraction more challenging) or because it will lower the chances of successfully conceiving . Even when women are able to access the treatment they need for their gynaecological condition, fertility services have been hugely disrupted by the pandemic, with many women and couples experiencing delays in accessing treatmentxxx.

The impact on women who felt their chances of conceiving and having a family were being reduced was significant, with many expressing feelings of sadness, anxiety and frustration. One woman said ‘I know that the longer it goes on untreated the more damage it's doing to my fertility. My chance to be a mother is dying inside me as this disease has taken over’.

Fertility problems and treatment often cause high levels of distress, and can have detrimental impacts on both mental health and relationshipsxxxi. The impact of not being able to conceive on an individual and their family can be significant in both the long- and short-term, and should be properly considered as one of the possible impacts of longer waiting lists in gynaecology.

Amelia is in her 20s and lives in London. She has just undergone surgery to remove endometriosis and a cyst, having been on a waiting list for over a year.

In September 2020, I visited my GP with heavy bleeding and chronic pain that had been going on for months. My GP was incredibly thorough and referred my straight to gynaecology, I then had two scans between then and August 2021, which confirmed I had endometriosis and an ovarian cyst. At that point I met with the consultant who said she wanted to do a laparoscopy to remove them both. I then waited for surgery, which I finally had in December of 2021.

Waiting for scans, appointment, and then finally my surgery was tough. My periods were so heavy I struggled to get out of bed, they made me lethargic and added to my low mood. I struggled with the pain, but was also conflicted because I didn’t want to take lots of pain relief day in day out. The cyst in my ovary felt like a ticking time bomb. From the pain it was causing and the size, I was really worried it was going to damage my ovary and effect my fertility. After my first scan confirmed the cyst and I asked what the implications were, I was told I could lose that ovary.

Waiting for the first consultation after that made me feel powerless, frustrated and scared. I had so many questions; could I lose both my ovaries and be put into early menopause? Will they just give me a hysterectomy? Even if I didn’t lose an ovary, would it just be harder to conceive in the future and if so what can I do about that? Should I be trying to have a baby now in case they take out my ovaries? I definitely didn’t feel ready for a child. I felt like every day the cyst was inside me I was getting more and more damaged. I just wanted someone to ask all those questions to and felt like I had no one to ask.

Misha is in her 30s and lives in East Anglia. She is on the waiting list to see a gynaecologist for endometriomas, which are delaying her access to fertility treatment.

After I got married in 2018, my husband and I started trying for a baby. After a while we started to become a little concerned that we hadn’t yet got pregnant. After a couple of years, and a conversation with our GP who frustratingly just told us to keep trying, we decided to get some tests done at a private fertility clinic. All of the tests came back with no concerns, other than a scan of me which identified what looked like cysts in my ovaries, and also showed that one of my ovaries sat behind my uterus.

The scan prompted my GP to refer me to see a gynaecologist, who I waited three or four months to see as an initial appointment, but didn’t really speak to me about my cysts and simply referred me on to see a fertility specialist. After waiting a while longer, our fertility referral was refused by the team because of a concern that they didn’t know enough about the endometrial cysts and wouldn’t be able to move forward with treatment until we knew if they needed to be removed.

I’m now stuck waiting to see a gynaecologist once again to investigate and decide on a course of action for my cysts, and until then fertility treatment is on pause. I know that if I do need surgery to remove the cysts I will have to wait even longer until I can access fertility treatment. It just makes you constantly anxious with all of the waiting. I’m so conscious of time, and the fact my fertility will be impacted the longer I wait. This whole process has already taken well over a year, after two years of trying to conceive. On top of all of this, the pain from the cysts continues to worsen as time goes on.

RCOG members reported concerns that longer waiting lists for elective gynaecology might result in fewer incidental diagnoses of suspected gynaecological cancers. The cancer diagnostic pathwayxxxii and the cervical cancer screening programme are designed to pick up the majority of suspected gynaecological cancers. However, members are worried that there were still routes for cancers to go undiagnosed via the elective pathway.

Firstly, there may be a proportion of patients presenting with malignancy or pre-malignant changes that are not picked up because of the length of waiting lists. There are a number of non-cancerous gynaecological conditions that are aligned with an increased risk of cancer, and therefore there is a potential risk of undiagnosed cancer if women with such conditions are on waiting lists for a long time without being seen by a gynaecologist.

In addition, there is also the risk of a misdiagnosis of a suspected gynaecological cancer in primary care resulting in a small number of women and people with cancer being incorrectly put on an elective pathway. Longer waiting lists for initial outpatient appointments and diagnostic testing on non-cancer pathways mean there is the potential for these cancers to go unrecognised for longer than usual. RCOG members shared examples of this occurring with ovarian cysts that were assumed to be benign.

The true number of women who have a delayed diagnosis of a gynaecological cancer is yet to be seen, and may not be significant. However, it is essential to recognise the added anxiety both to women and to clinicians created by any perceived risks of cancer going undiagnosed, and to consider ways in which these risks can be mitigated as part of recovery planning.

Jayne is in her 50s and lives in Wales. She was diagnosed with Lichen Sclerosis in March 2021.

When I was diagnosed by my GP with lichen sclerosis, I was given cream to manage my symptoms. The cream did not feel like it was working, and I really had to push my GP to get a referral to gynaecology, because I had terrible issues with fusion of my labia, I’ve lost a lot of structure around my vulva. I’m now on a waiting list to see a gynaecologist, but I don’t know how long I’ll have to wait. I’ve had a letter but all it told me was that it would be a very long wait.

Supposedly you are meant to have six month check-ups to monitor this condition because of a cancer risk, and there’s been nothing. I just worry about that. I don’t feel like I’m getting the care I need from my GP either, they are just not there for me at the moment.

I know it’s not life-threatening, but it’s having such a huge impact on my life. It’s so painful I can’t walk very far, and I’m leaving the house far less. I can’t have sex anymore because it’s too painful, and that’s been taken away from me not by choice. I feel as if I’ve been abandoned and not listened to, like I’m just expected to get on with it.

RCOG members taking part in our survey and interviews reported an increase in the number of emergency admissions among women on a waiting list for planned care. Members told us that patients were coming in through A&E with conditions that required acute care, in particular anaemia caused by heavy menstrual bleeding, and women in acute pain caused by endometriosis or ovarian cysts.

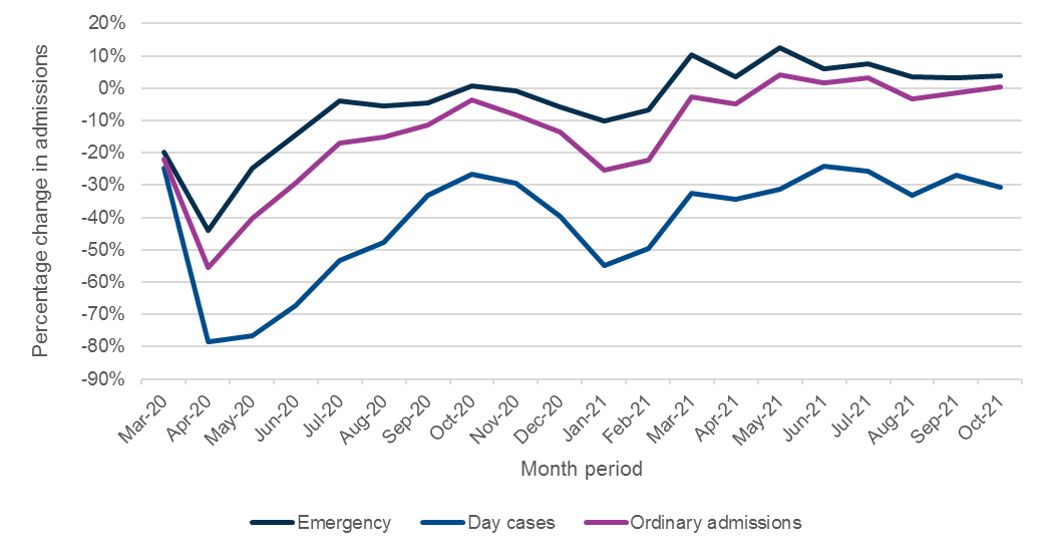

Analysis shows that emergency admissions have been marginally above pre-pandemic levels for much of 2021, which aligns with members’ experiences. As this data is not broken down by region, it is also possible that more significant changes in regions with longer waiting lists are being masked in the national data. The RCOG would support further breakdown of the data to explore this possibility.

Figure 6: Change in gynaecology admissions (%) since March 2020 by type when compared to the average admissions March 2019-Feb 2020

Mollie is in her 40s, and she lives in the North West. She was waiting nearly two years for a hysteroscopic resection to remove her fibroids, which she had in late December of 2021.

At the end of 2019 I was taken in to the emergency gynaecology unit with a very heavy bleed and needed a blood transfusion. It was just at the time that I was going through the motions with the local gynaecology unit following a referral from my GP, and I’d recently had a diagnosis of uterine fibroids. Following my trip to A&E, I was flagged as urgent. I was put on a hormone medication called Norethisterone to manage my heavy bleeding in the meantime.

Once I’d seen a gynaecologist a few weeks later they sent me for an MRI to see whether I would be a good candidate for Uterine Fibroids Embolization (UFE) to shrink my fibroids. It was just after that scan that the pandemic hit, and I was sent a letter saying that UFE wasn’t the right treatment for me, and that because of the pandemic they weren’t going to take any immediate action until after non-urgent care had started back up again, I waited over a year to hear anything further.